This page is an open forum for you to share your thoughts with colleagues.

Please consider submitting a brief blog with perspectives about our lives in medicine.

Blog anonymously with minimal descriptive information, or with your name.

Submit to pwp@TCMS.com

Submitted April 2022

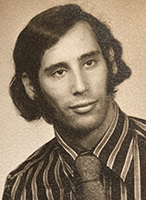

by Dr. Quintin Smith

MEDICINE’S GOLDEN AGES

I recently participated in my second Zoom session with third and fourth-year medical students at UTMB, now the John Sealy School of Medicine. It is a Practice of Medicine seminar provided by the school to help give them insight into what specialties they might wish to go. Alumni are asked to answer commonly asked questions as well as offer advice from their perspective, provided from colleagues ranging from early career to retired. Having retired in 2013 after forty-two years in Ophthalmology, you will easily see which category I fit into. In thinking about answers to the “most frequently asked questions” from each year, I am struck by how sincerely the students seek insight and perspective from those who have preceded them. I have been thinking about how this observation relates to the future of Medicine both for these future doctors and those physicians still in the “trenches.”

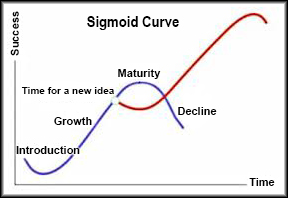

When I acquired my practice from a retiring colleague, I told him he was retiring at the end of the “Golden Age” of Medicine. Little did I dream of the changes which were to occur in the ensuing years! These future doctors are concerned with many issues but I think “Work-Life Balance” is a priority. At a time when Medicine is struggling with physician “burn-out” and “resilience,” perhaps their concern is well founded. Their training seems to be orienting them toward more teamwork in patient care which may reduce stress. Medical care itself may ultimately be largely provided by paramedical personnel with the role of the physician quite different from what it is today. Perhaps at this time, currently practicing physicians’ “Golden Age” is coming to an end and they will have to accept new paradigms if they are to reach happy retirements. The question is, can today’s physician make the necessary changes? Many practices employ paramedical assistants who deliver significant quantities of care. Undoubtedly, adjustments in lifestyle have been made by physicians as reimbursement levels have changed. Those who have been able to retire have done so and others are considering retirement.

Perhaps the bigger question is whether today’s physicians can accept the inevitable changes, adjust to them and derive pleasure from the remainder of their medical careers? Without doubt, the efforts by our professional organizations to reduce the administrative chaos will help enormously. Physicians still practicing a traditional style of medicine will need to evolve with the times if they are to survive, much like retail businesses faced with the efficiencies and conveniences of their online competition. Hopefully, in the midst of this evolution, they will be able to maintain our traditions of healing. One day most of us may be able to look back at our own “Golden Age,” and for those future doctors, it may be yet ahead.

Quintin J. Smith, MD

qsmith13@att.net

Submitted April 2022

by Dr. Michelle Owens

The Mama Bear Instinct

As a mother of 2 little ones, I’m starting to understand what the mama bear mentality is. Protecting them, advocating for them and doing whatever I can to ensure they have what they need to thrive, survive and enjoy this life.

I started to think about what if we were not only mama bears for our children, but also for ourselves? Imagine - empowering and supporting yourself to be the best that you can be, nurturing yourself and showing compassion and grace in the face of disappointment, advocating for and protecting yourself against toxic situations, people and environments?

This sounds like it could be called fierce self-care.

And all the while we would be modeling these healthy and important behaviors for our children, our partners, our friends, our colleagues, our communities and our world.

If we don’t advocate for ourselves, who else will?

We have to be willing to take care of ourselves, in order to be able to continue to care for others, in whatever capacity that may be.

You have to be a mama bear for yourself. ❤️

Michelle Owens, DO

Physician Wellness Program Co-chair

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted, March 2022

Brian S. Sayers, MD

An Officer of the Court

Tony (not his real name) was one of those patients who came to be a friend. I was his doctor for 11 years, guiding him through some very difficult times with a chronic autoimmune disease. He was a handyman, a fly fisherman, husband, father and a man of deep faith. His condition was difficult to control but he always offered a smile as he patiently and hopefully waded through a series of treatments through the years. I’m a terrible fisherman, neither of the two necessary traits (patience and reading the water) coming naturally to me, but it didn’t keep him from giving me flies that he had tied himself, even giving me a handmade bamboo fly rod that to this day sits in my study unused but treasured.

One afternoon my receptionist urgently pulled me out of an exam room, concerned. “There’s a man in the waiting room, a deputy or something, and he wants to see you… he has some papers.” To this day I’m not sure who or what he was other than a messenger of misery. I suppose he was a constable. He handed me the papers, and I vaguely remember a badge, a gun that seemed entirely unnecessary and a decidedly unsympathetic look, a preview of the stress and self-doubt that the coming months would bring.

I hadn’t seen Tony for quite a while and it turned out that he had been diagnosed and quickly passed away with an aggressive malignancy that a plaintiff’s attorney seemed pretty sure several of my colleagues and I should have divined, even in the absence of any signs of it when last seen. This was some years back, in the era before tort reform in Texas, an era where hardly anyone knew a physician who had not been sued at least once. Now it was my turn.

If you haven’t been through it, it’s hard to understand the emotions you go through during malpractice litigation. In some ways it attacks the very core of who you are as a physician, an accusation that you are doing exactly the opposite of what you swore an oath to do and spent all those years training to do well. There was a strong sense of injustice, as I knew I had really done nothing wrong. I was forbidden by counsel to discuss it with friends or colleagues, adding an unhealthy serving of isolation to a plate full of shame and anger. To complicate matters even more, I was simultaneously grieving a man who I considered a generous friend. After a year of silent anguish, second-guessing myself and being suspicious of patients I once felt at ease with, I was as unceremoniously dropped from the suit as I had frivolously been added in the first place. There was a tremendous, but profoundly incomplete, sense of relief. Now even two decades later I still recall those emotions clearly, even as I ironically still treasure the fly rod Tony gave me.

As physicians, we are called on to be many things by patients, and by ourselves. Compassionate, competent, vigilant, intelligent, patient, available, and when lives are in the balance, perhaps even perfect. Litigation, deserved and undeserved, remains a constant threat lurking behind any mistake or just bad luck, but fortunately not as much as some years back. This extreme kind of judgment against us has to some extent been replaced by 100 smaller cuts that we face from criticism from patients or their families, online reviews, peer review, insurance authorization denials, peer to peer reviews, colleagues, employers, practice managers, and at times, most damaging of all, from ourselves. Some of these criticisms are well-deserved, even constructive, and are to be carefully considered as teaching moments, while others are simply based on bureaucracy, greed, frustration or just nastiness. All of them challenge our deep and ultimate calling to bring compassion and love, along with our talents, to each and every interaction with our patients. We have to be careful, through self-reflection and support from colleagues and loved ones, that this type of criticism does not harden us over time in a way that causes us to lose the compassionate calling that a younger version of ourselves set out to pursue all those years ago.

Brian S. Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Submitted March 2022

by Dr. Michelle Owens

What will fill your cup and feed your soul today?

Self-care is not one size fits all. On social media, there are a variety of memes and lists on ways to practice self-care. I’ve noticed these memes and lists seem to primarily contain yoga, meditation, massage, and candlelit baths. Between my husband and me, self-care can look very different, so I’m sure it looks different for others too. Being an Austinite, I think we need a “well-being food truck” with a menu of self-care items listed for people to choose from. Then we can ask “what will fill your cup and feed your soul today?”

Maybe it’s listening to one of your favorite old-school jams or meditating for 5-10 minutes. Maybe it’s calling a friend to say hi or sitting in silence hidden away from the world. It could be practicing gratitude, soaking in a tub with your favorite beverage and show streaming in the background. Or cuddling with your fur baby, bathing in nature, eating fresh pineapple or your favorite sushi, putting pen to paper and letting your feelings flow, or chatting with your therapist. Or maybe it’s a host of other things that aren’t mainstream, and that’s OK. Whatever speaks to you and helps you to refuel is personal; we don’t have to have the same definition of what self-care means or looks like as everyone else. And most importantly, each day and maybe even each hour, we may need something a bit different.

Let’s share with each other what self-care looks like, and maybe we will all be able to add a little something new to our favorite self-care menu.

Michelle Owens, DO

480-734-1110

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted March 2022

by Dr. Brian Sayers

Hope Floats

These last two years have affected us all in different ways, but for some, something positive in this long ordeal has been long overdue reflection and a reimagining of our work or relationships. It’s easy to get caught up, sometimes for years at a time, in routines that deplete us, and sometimes we feel unable to make much needed steps towards change, only to feel stuck, even helpless. I hear stories about this from many of our colleagues in my work with PWP and have great admiration for so many who have made much needed life changes that often go against the institutional culture of medicine and our own bad habits. Much needed change snuck up on me when I realized that I was just terribly inefficient with telemedicine in those early days of the shutdown. Appointment slots were lengthened, something I found myself unwilling to undo once I went back to seeing patients in the office. With a lighter schedule my days are less chaotic and stressful, and I came to love my work again. I’m nearer the end than the beginning of my career, my kids are off the payroll and I’m self-employed so admittedly I am able to make changes that will make my work more sustainable in the years to come that not everyone can. Still, I have to shake my head that it took me so long to realize the trade-off is well worth the bottom-line sacrifice.

To further confound my financial planner, we bought a little farm an hour or so from town during the shutdown. It’s been a steep learning curve of wells and septic fields, irrigation systems and permits, spiders and snakes, but I fell in love with the old farmhouse and the olive grove that covers much of the property. The previous owner planted 200 olive trees years ago that flourished until the big freeze of 2021 killed off about a third of them, most of the rest severely damaged. This past year after we purchased it most of them have started growing back as shoots, four or five feet by now. It’s a metaphor for our own recovery from these last two years, but I’ll set that aside for now. Relaxing there and not worrying about patients quickly morphed into worrying about the grove, but it’s different and there is satisfaction in watching life being breathed back into the place, ever so slowly. I wander and tend to it weekends and have made each of my grandchildren adopt a couple of the struggling trees, measure and talk to them when they visit.

It’s an experience that has made me reconsider hope. I can imagine how people who farm or ranch for a living center their lives around hope each year, just as we do when we look at our children or grandchildren, or a patient, friend or family member who is struggling or ill, or when we wish our workdays would nourish rather than exhaust us. Hope is the underlying current in optimism, the wind in the sails of our lives, and without it we are set adrift. These last two years have given me a chance to reconsider what I hope for, sometimes pray for, and what I should let go of.

The drive to the grove is about the right distance to unwind and, for the moment at least, leave the worries of Austin behind. About 15 miles from my turnoff, I pass by Smithville. There is a sign on the highway announcing “Smithville, Home of Hope Floats.” It was a popular movie filmed there that most of you have seen, a story about humility, divorce, childhood trauma and death of a love one, but in the midst of it, from the ashes, a new family, happiness, wisdom and hope emerge. I watched it again recently, trying to remember the line in the movie that the title comes from. It is at the end when Sandra Bullock’s character notes, “Beginnings are scary, endings are usually sad, but it is the middle that counts the most…Just give hope a chance to float up, and it will...” The sign is badly faded and whizzing by a bit above the speed limit all I see each time is the reminder that “Hope Floats.” And that is enough.

Brian S. Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

From the Other Side

As I sit at the bedside of my grandmother, she is on her final journey out of this world and I am reminded that life goes on despite the hardships we navigate.

Golden Girls is playing in the background – a show I grew up watching with her every time I’d visit.

I am a hospice physician – my day job is helping to ease suffering and allowing for a peaceful death. Yet being on the other side as a family member is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

I reflect back on my journey into medicine and how I ultimately decided on pursuing a career in hospice and palliative medicine. The experiences throughout my education colored my path to be able to navigate this exact moment. I truly feel I’ve been preparing my whole life for this moment – to truly advocate for my grandmother and know what to ask for, to comfort my family and gently deliver the news that she’s dying, to understand what terminal delirium and agitation look like and hope to give myself the compassion and grace I tell my patient’s families to give themselves when faced with a similar situation. Yet knowing all these things, I still struggle.

I am in awe of the beauty of the gift of time. How fleeting it comes and goes. Although I am reminded daily in the work that I do that we are not promised tomorrow, this impending loss is not any easier.

Our life experiences shape us into who we become and our losses remind us of the beauty of being human, knowing suffering, and holding love and loss in tandem. I will forever be changed after experiencing this loss. I now understand even more how devastating and debilitating loss can be.

My grandmother’s death will make me a better physician, mother, wife, daughter and friend. As they say, it’s better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all.

Dedicated to my grandmother, Blanche Beverly Owens (1932-2022)

Michelle Owens, DO

Co-Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

mowensdo@gmail.com

RECLAIMING JOY

I watched as her face glowed with excitement as she told me her MCAT scores. Her prospects of being accepted into medical school had just increased. This was her third attempt at the MCAT. She is a patient care technician who works in my hospital. We shared the same patients on many occasions. She had made efforts to seek my company whenever I rounded. As I looked at her face in her excitement, I remembered my own. Unknowingly, she gifted me with the memories of that time when I fought to enter our profession. I immigrated to the US at the age of 8. English was my third language. Because of this language barrier, I struggled with the MCAT. It was not the only barrier. My birth country and culture did not support women in higher education. In addition, my parents were poor immigrants themselves and I had to work my way through college and medical school on my own. Yet, I was not deterred. Acceptance into medical school was one of the joyous highlights in my life because it had been such a struggle.

Somewhere along the way, like so many of you, I forgot all of that and lost my joy as a physician. The workload, long hours, heavy responsibilities, electronic records, and attempts to meet impossible metrics squashed my love for medicine. Fresh from training, I had joined 3 other men in an internal medicine practice in Kansas. I remembered the oldest of the 3 men in his 70s said to me on my first day of practice, “I am sad for you joining medicine these days with such a broken system.” Over the next 2 decades as a hospitalist, I realized how true his words were. These past 2 years during the pandemic worsened my attitude. Going to work every day felt heavy. I vacillated between anger and sadness.

In sharing her new MCAT scores and her excitement, my young friend suddenly brought me to a place of gratitude. I remembered the difficulties and remembered where I was and where I am now. It was as if a switch was just turned on. I remembered the excitement of scrubbing in for surgery for the first time, delivering a baby for the first time, placing a central line for the first time, intubating a patient for the first time, and being called “doctor” for the first time. My eyes were wide open. My mind had the humility of a beginner. Back then, no one could take my joy away.

So, what happened? I could name all the things that I feel took away my joy for medicine. Trust me, it would take a whole lot more than these pages could hold. I am not so “Pollyanna” that I do not see the destruction of our health system. Nor do I deny that anger doesn’t come up when I witness the atrocity physicians must go through to care for their patients. However, I am at a place where I am sick and tired of being sick and tired. I have decided no one can take away my joy. I am no longer willing to give the power and control to another or a system. I get to reclaim it.

I started to reclaim my joy of medicine by remembering what brought me here in the first place. For me, it is the art of medicine itself and the connection with patients and colleagues. I felt thrilled to be able to diagnose the unique unilateral hyperhidrosis and vertigo associated with a stroke. I “get to” sit down with a stage IV ovarian cancer patient who failed treatment as she taught me the art of dying. I get to brainstorm with colleagues on challenging medical problems and finding shared vulnerabilities of “I have no idea what this is.” I consciously chose facilities and hospitals that value my work. I chose practice partners that share the same philosophy in medicine and support my need for time away. I cut hours of working so I can tend to my own healing. It is in these things that I find joy while still working in a broken system. I have learned after nearly 3 decades in this profession, there is never a right time to make changes. If I don’t do it now, it may never happen. As a physician working in acute care, I learned life is fleeting.

My young friend was accepted into the medical school of her choice. She did not have to say anything. I saw it on her face. I saw and felt joy.

This quote by Josh Shipp summarized it all for me: “You either get bitter or you get better. It’s that simple. You either take what has been dealt to you and allow it to make you a better person, or you allow it to tear you down. The choice does not belong to fate, it belongs to you.”

Dr. Anna Vu-Wallace

annavuwallace@gmail.com

Friendship

This weekend I was putting together some promotional material to introduce TCMS members to the PeerRxMed program, a buddy system to help physicians connect and support each other one-on-one on an ongoing basis. As we have tested the program, I found myself reconsidering the importance of connection in general and more specifically the nature of friendship. It’s an important topic these days and much has been written about the high percentage of doctors who feel isolated, the “Loneliness Epidemic,” and the known physical, professional, and emotional consequences of isolation that have been extensively studied recently.

Isolation from friends and colleagues is not a new problem. In fact, some authors argue that physicians by the nature of their training and work are more susceptible to it than most, and for many maintaining connections has been made worse these past two years. Maintaining, let alone nurturing or developing, new friendships and meaningful, healthy connections takes effort, time, emotional energy, and more recently, not just a little imagination. With so much at stake in having not just acquaintances, but true friends in our lives, it’s worth considering the nature of friendship and what friends should be for one another. David Whyte describes friendship and the consequences of neglecting them this way:

“…the ultimate touchstone of friendship is not improvement, neither of the other nor of the self, the ultimate touchstone is witness, the privilege of having been seen by someone and the equal privilege of being granted the sight of the essence of another, to have walked with them and to have believed in them…on a journey impossible to accomplish alone. An undercurrent of real friendship is a blessing exactly because its elemental form is rediscovered again and again through understanding and mercy.

...a diminishing circle of friends is the first terrible diagnostic of a life in deep trouble: of overwork, of too much emphasis on a professional identity, of forgetting who will be there when our armored personalities run into the inevitable natural disasters and vulnerabilities found in even the most average existence.”

We ignore our friendships and their vital importance in our lives at our own peril, both individually and as a society. Mother Teresa observed that many of the world’s ills are a result of having “forgotten that we belong to each other.” Deeply connecting and sharing not only life’s joys but also our challenges and fears is not a sign of weakness, rather a profound form of personal and collective strength.

Whether you participate in the PeerRx program or not, find ways in your busy days to connect with friends and colleagues on a regular basis. You will absolutely make a difference in their lives, but also consider, as Gregory Boyle notes in Tattoos on the Heart, that this act of friendship - of kinship - is “not serving the other but being one with the other.”

Brian S. Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Standing on Holy Ground

One of my favorite passages from sacred writings is the story of Moses, still tending his father-in-law’s sheep, an ordinary day in an ordinary place, suddenly encountering God, the ground he stood on now consecrated into holy ground, admonished to “Take off your sandals, for the place you are standing is holy ground.” All of the world’s religions speak of holy ground. For Muslims, even the simplest prayer rug in the humblest of places becomes holy ground to commune with Allah. Buddhists may have a transcendent experience at a stupa. The concept of holy, or sacred, ground transcends religion and in a secular sense people commonly find themselves encountering a different spiritual plane in all kinds of places. The experience may sneak up on you, but requires open eyes to be receptive to it.

Some years back, my wife had an appointment with a specialist at Southwestern in Dallas where we would receive more news about a diagnosis that would forever change our lives in so many ways. While she was waiting to be seen I went back to the medical school auditorium where I spent so many transformative hours all those years ago. The room had many technology upgrades over the years but it was still much the same. I considered my own time there and the fact that the doctors Maryann was seeing next door all would have either trained or taught in this same room, and I had a sense of an almost mystical nature of this ordinary room, of all the lives changed for those who passed through its doors. Similarly, a patient of mine recently described such a feeling when visiting the military cemetery at Normandy. The se spaces can outwardly be ornate or very ordinary, ground that becomes extraordinary and carries with it a moment in which we seem to commune with something beyond ourselves – a favorite place in nature, working in a food bank, quietly nursing a baby.

So, how might we describe holy ground in ways that may be recognizable, even familiar, to all of us regardless of whether we appreciate its presence with religious, spiritual, or purely secular eyes? Some describe it as a “thin place,” something the Celtic tradition describes as a place where the space between the material and the divine becomes very small, where the concrete merges with the infinite, where our tangible, practical world is suddenly enveloped with mystery and intangible truth. Where, for a time, we feel untethered and are united with a hidden world and souls around us. As with Moses, or the prayer rug, the stupa, even an auditorium, the terrain itself may be ordinary, but what happens upon it, or what it comes to signify makes it sacred.

In health care, presumably there was an original sense of calling to heal, a calling that you answered years ago and still follow. For all of the things that get in the way of us pursuing it well, we are still incredibly privileged to inhabit the holy ground on which we meet our patients, people on a common journey with us, who literally and figuratively bare their bodies and souls before us, with trust – with an assumption that we will come to them with humanity, compassion and fidelity, to stand on this ground, and as we do it we agree to leave behind the encumbrances and baggage that we all carry. For the moment, we leave it all at the entrance to this sacred and mysterious space.

Pause at the door, take a cleansing breath, then enter the exam room, or hospital room, ER cubicle, or operating room. Take off your sandals, you are standing on holy ground.

Brian S. Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Photo credit: Ashley Yeaman, Focus Magazine

The Covid Chronicles…

Submitted November, 2021

by Dr. Leslie Cortes

COVID Apocalypse

Almost from the beginning of the pandemic, I have referred to it as the COVID apocalypse. I use the word apocalypse in both its secular meaning of disaster or catastrophe as well as in its original meaning from its Greek root for uncovering or revealing. With the first meaning, I refer to the toll of illness and death as well as the disruptions of societal functions and global economics that the pandemic has caused. The latter meaning refers to the unmasking of things both good and bad.

Most of the good that the pandemic has revealed has been at the individual level, I think – compassion, service, altruism, and self-revelation – a better understanding that we each have of ourselves and what is important to us. Much of the bad revealed has been at the organizational and structural level – inequity, inequality, greed, and callousness. These things have always been with us, but the apocalypse has laid them bare. It has revealed how politics taints public health decisions, how political rhetoric taints the decision-making of individuals who profess to live by the Golden Rule as well as the decisions of our public institutions that profess to serve us all.

It has pulled back the curtain on pretenses to reveal how corporations that claim to be engaged in making us all healthier readily put profit above probity. It has revealed the hypocrisy of expressions such as “essential workers” when they are used to apply to healthcare workers and first responders but not the workers who keep our pantries stocked, our utilities on, who teach our children, and who make life seem normal despite the ongoing conflagration. These are the workers who make it possible for those of us, more privileged, to work from home, shop from home, and otherwise minimize our exposure to potential infection.

I am among the privileged because my wife and I are retired with a secure income; many Americans are not. I am among the privileged because my wife and I are vaccinated; most of the world is not. I am among the privileged because of an accident of birth, a helping hand from many I have met in life, and an occasional fortunate decision rather than because I deserve it. For these things, I am grateful.

Leslie L. Cortes, MD

llcortes55@gmail.com

Submitted November, 2021

by Dr. Michelle Owens

“What are your goals of self-care?”

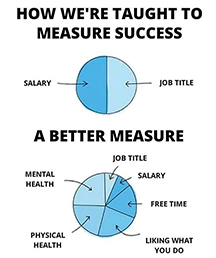

"This graphic made me say “Yes! Yes! Yes! 1000% this!”

In hospice and palliative medicine, one of our most common interventions is a goals of care conversation – like an appendectomy for a surgeon or a tonsillectomy for an ENT. A goals of care conversation explores what patients value most in life and helps to guide their medical care in a way that meets their specific life needs.

In the 5 years I have been practicing, I’ve realized that these goals of care conversations actually translate across most areas of life – not just at the end. In fact, you could consider many of the questions asked could be part of a “goals of self-care” conversation. What better way to guide our decisions and provide a better measure of what a successful life looks like?

Think about this for a moment:

Instead of asking “what are you willing to go through to get more time?” to a person living with serious illness, we might ask ourselves, “what are you willing to go through in your work life to be able to maintain your home life balance?” Or “what are your work life and home life non-negotiables?”

The question “what do you want to do with whatever time you have left?” is appropriate for all of us at any time.

The questions “what brings you joy?” and “what gives you strength during hard times?” are also appropriate for us to reflect on.

The only things we are promised in life are change, taxes, and death. We are tasked with being good stewards of our energy and living this life to its fullest.

What other questions could we ask ourselves to ensure we are living the best-balanced lives that we can?

I encourage you to start your own goals of self-care conversation.

Michelle Owens, DO

mowensdo@gmail.com

The Covid Chronicles

Submitted by Dr. James Marroquin

November, 2021

On a winter trip to New Mexico earlier this year, our family hiked to a frozen lake. My sons Elijah and Micah threw rocks at the water and watched the surface crack. They then hurled sheets of ice they created, shattering them across the lake. Even as the cold turned their hands beet red, they couldn’t get enough of this chilly activity.

Watching their carefree sense of wonder and fun, I reflected on my very different mindset in middle age. These days I feel the need to ensure every moment of my day is purposeful. When a gap opens up in my schedule, my first thought is how it can be usefully spent. A positive way of framing this is that I’m being a good steward of my time. But there are less flattering interpretations of this quest for perpetual productivity. Am I seeking to make myself feel important? Am I distracting myself from uncomfortable realities?

To become physicians, we put in long hours, sacrificing time with friends and family. We were conditioned to make work our highest priority. For many of us in clinical practice there are always more tasks to be done. And the portability of the EMR enables us to continue the grind even after we’ve arrived home.

It’s challenging to put limits on our work--to set apart and protect time to rest, play, connect, and savor our lives. Some doctors unfortunately don’t have control of their work schedule. But even if we do, it’s easy to view these “non-productive” parts of our lives as less worthy of our time and attention. With growing levels of burnout worsened by Covid, it’s vital physicians spend our days in ways that enable us to thrive in our lives and not just our work.

For me that’s included around ten minutes every morning outside gazing at the sky. I notice the trees swaying, clouds shifting, birds chirping, wind chimes clanging, and the sun slowly rise. Sometimes my golden retriever Hunter even comes by for a pet.

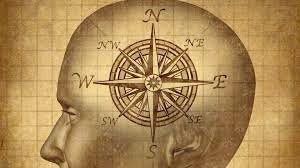

I’ll end with a powerful exercise from the social scientist Arthur Brooks. First, imagine yourself in five years. Picture yourself as happy, whatever that means for you. Next, list five things that made you happy five years from now. Place them in order of their importance in bringing you joy. Lastly, ask yourself how to best manage the two most important priorities on your list. How can you invest in them to enable them to grow and flourish?

Dr. James Marroquin

jamesmarroquin@gmail.com

Submitted October 27, 2021

In These Silent Days

I’ve been trying to make sense of anonymously submitted surveys that colleagues fill out when they access the TCMS Safe Harbor Counseling Program. With over 1000 counseling visits funded so far, there is a lot of data, and I am poorly equipped to analyze it. Two of the questions ask: “Please rate your satisfaction with your work,” and “Please rate your satisfaction with your relationships outside of work.” We’ve seen over 97% of respondents express satisfaction with the therapy they have received, but no convincing data that they are accessing counseling primarily because of dissatisfaction with work or relationships.

My original thesis debunked, why then do physicians access counseling? It’s a question worth considering as we’ve seen a dramatic rise in utilization of the program during the pandemic, especially starting around the first of this year and again in August after so many months of challenge.

I’ve asked psychiatry colleagues and therapists their perspective on why our colleagues seek therapy. A therapist I trust pointed out something that should have been obvious. Many of our colleagues come to therapy not just with stressors from work and relationships, but rather, in this unique and prolonged time of challenge, they come to therapy in the midst of a sort of “stalled discernment,” a sense that change is needed, but without clarity of what that should be or how to pull it off.

For most, these many months in pandemic, especially the early ones, have been times of upheaval and uncertainty, a vague anxiety and loss of balance ever present in the background of our work and family life. But more importantly, it has been a time that cries out for us to identify foundational things that make us whole and open our hearts. Intermingled with the chaos have been moments or days of reflection and reassessment. For many, it has been a time of discernment as we consider where we were in our frenzied pre-shutdown lives and how we might reimagine our future. A time to assess what is nourishing and life-affirming and what must be left behind. The results are all around us. In our own lives and those of countless colleagues there has been a realignment of family life, and in the workplace, unprecedented numbers retiring, leaving clinical practice, changing practice settings, or otherwise trying to make their work sustainable for themselves and their families.

Singer/songwriter Brandi Carlisle calls this time, “these silent days,” noting that “either way, I lose you in these silent days…” perhaps meaning we will all be different in some way or another as a result of these past months. Shedding the old is always a part of becoming new. Writing in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Ranna Anwash observed it in a similar way:

“If we are to find a way to live our values in these demoralizing conditions, we must hold on to what is nonnegotiable in ourselves—not because it will heal our patients but because that is the only path back to ourselves. And, yes, it will be a different version of ourselves that we meet on the other side of this. One that no longer believes in neat and tidy happy endings. Someone with perhaps a little less faith and who is still in need of healing, but potentially—hopefully—someone we recognize.”

Henri Nouwen described discernment as “reading the signs of daily life,” of seeing − and recognizing − ordinary and extraordinary events of life as signposts for both the present and the future. Discernment goes far beyond decision making. It is about rediscovering core beliefs and values, joyful living and the things that breathe life into us, then making them the defining movements in our lives, something at once difficult and essential.

Brian Sayers, MD

bsayers@austin.rr.com

The COVID Chronicles

Submitted by Dr. Kim Wheeler

October 2021

Small Town Covid

In March 2020 I joined a TMA Teleconference regarding a virus called COVID19 that was in China. The TMA called all members that night with an update. As I listened, I almost dropped the phone as we were notified that the virus was among us and would become “The pandemic of our lifetime.” We were also notified that PPE and testing supplies were scarce so in essence “Good Luck.” And the TMA was correct. COVID19 had arrived. Within days our small-town family medicine practice had implemented telemedicine, put strict office mask and sanitation protocols in place, obtained as many PCR swabs as possible to start curbside testing, and went to two shifts so if one shift had to quarantine the other shift could take over. We worried that we would become infected and infect our families. We went to work every day and never missed a beat. In December, we were overjoyed as we were offered vaccines. There was a sense of relief that we could do our jobs safely now. We provided hundreds of vaccines to our patients. In June, the CDC was giving a positive outlook and we were feeling hopeful.

Then July hit. We started seeing a surge of COVID that was worse than 2020. We were tired and unprepared for seeing anything “worse.” By August we were booked a week in advance and had dozens of “COVID positive” patients calling daily for appointments and infusions. Most were unvaccinated, but we were alarmed to see vaccinated patients testing positive as well. By October 2021 we have had hundreds of patients infected with COVID19, many have been hospitalized, and unfortunately many have died. We’ve seen families lose multiple loved ones. It has become part of our lives, part of our daily discussions with patients.

BUT . . . w e are becoming hopeful again. Vaccines are easily accessible and boosters have begun. Children under 12 will soon be able to get their vaccines. There is talk of a pill for COVID that is being developed by Merck. Many unvaccinated patients who got COVID during the surge now plan to get vaccinated. There is a faint light at the far end of this tunnel. We cannot give up. We have come too far. We care too much. This is what we do.

Kim Wheeler, MD

Lockhart Family Medicine

wheelerk4@yahoo.com

Submitted by Dr. Tyler Jorgensen

October, 2021

Seeking Still Waters

Whitewater paddlers make it look so easy—staying upright in raging waters, navigating huge swells, leaning and cutting hard at just the right time to avoid dangerous obstacles. And when they do flip upside down, they are able to pop themselves right back up. It’s a marvel. But no matter how expertly they paddle, they always have to respect the power of the water. The moment they let their guard down and get too comfortable, they can make a careless and costly mistake.

We physicians do the same. We take an inherently dangerous, complex, and difficult discipline and learn to practice it as an art. We learn how to navigate tricky diagnostic pathways, respond rapidly to changing clinical conditions, and try to stay emotionally upright while riding successive waves of an ongoing pandemic. On our best days, we glide through the whitewater of medicine with style and grace. But if we let our guard down and get sloppy, we can end up making a careless and costly mistake. Who of us isn’t fatigued by constantly having to be on guard in the whitewater?

I have been thinking a lot about paddling lately. Getting out on the water has remained a source of wellness and renewal for me since residency. I enjoy just about all paddle craft. Sometimes it’s sitting inside a skirted kayak at the level of the water and flipping upside down only to pop up again—a sort of natural baptism that puts us in fellowship with the ducks and the turtles. Or maybe it’s hopping on a stand-up paddleboard on Lady Bird Lake, and immediately feeling carefree, relaxed, and untethered. Other times it’s paddling a gracefully-curved canoe with a friend, such a timeless and grounding adventure of shared effort and striving, shared wonderment, and sometimes shared suffering!

My current kayak is an unusual one—a black, open-hull, lightweight carbon-fiber downriver racing boat. At nineteen and a half feet long and twenty-one inches wide, with gunwales just a few inches off the water, it is super tippy. I have unintentionally flipped and flooded it many times. This boat was designed for racing down the San Marcos River, but I am still just trying to keep it upright in still water. To do so I am learning how to engage my core at all times and work on balance. No false or careless moves. It forces me to slow down and focus on my breathing and movements in ways no other boat has. I am enjoying the challenge.

Regardless of paddle craft, I have yet to spend a day on the water with a friend that didn’t result in fantastic conversation and deep connection. Hours on the water in nature together steadily take us to unhurried and thoughtful exchanges, along with potent periods of shared silence. Neither have I spent a day alone on the water that didn’t result in greater inner peace and calm. Meditation, gratitude, joy, wellness.

Here in Travis County, we are surrounded by waters. If you need a new wellness strategy, can I recommend getting out on the water? Whether it’s Lady Bird Lake, the San Marcos River, or a quiet section of Barton Creek, the water always buoys me up, helps me find balance, refreshes me, and draws me into deep connection. It can do the same for you. There is even growing neuroscience to show that bilateral alternating movements (like paddling) can help our brains process trauma. And we all know the countless benefits of time in nature.

As thrilling as whitewater can be, these days I find myself seeking still waters. Even while at work, in the midst of busy whitewater days, I am coming to find moments of still water. If I seek out and recognize these moments, slow myself down and work on my breathing, I re-discover the balance and form to keep me paddling downstream, staying upright in the everchanging waters of practicing medicine. I hope to see you on the water.

Tyler Jorgensen, MD

tylerscottjorgensen@gmail.com

By Dr. Brian Sayers

Harvest

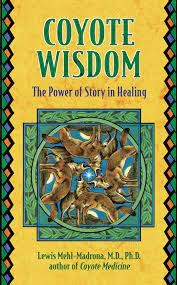

A long time ago, I spent three years in Albuquerque doing an internal medicine residency, years spent at the county hospital, a Public Health Service facility serving the Navajo and a regional VA. Those were good years, a time of learning how to care for people − once I figured out how to keep them alive. Strange as it sounds, one of my best memories of those days was eating on the patio of the VA cafeteria. They made the most amazing green chile stew, full of chile softened by hours of simmering, with pork, vegetables and spices thrown in. I would look forward to lunch throughout morning rounds. We sat together at a communal table, sharing stories about the strange cases and people we were caring for, quirky attendings, stupid mistakes, saves and codes, turfs and lack of sleep. We were all navigating southwestern and Navajo culture with varying degrees of success. We were learning the importance of understanding people’s culture in order to care for them successfully.

I soon learned that the chile harvest was the pulse of life in New Mexico. Fall in northern New Mexico was all about hot air balloons, the chile harvest and the communal celebration of both, with morning skies full of colorful hot air balloons rising in the high desert sunrise. Throughout the state, chile farmers would proudly bring their harvest to market in tourist towns, small villages and roadside stands, ready for cooking or decoration.

In the southern part of the state, commercial growers produced huge crops, mostly bound for Louisiana and the inside of hot sauce bottles. But in northern New Mexico, the norm was small family farms that have grown chile for many generations, the hard labor of growing chile an integral part of the culture, the rhythm of daily life and an ingredient in almost every meal. These small family farms were largely owned by folks with deep roots there, many direct descendants of Spanish colonialists with strong Native American heritage. They have worked the land and passed it and their way of living down through uncounted years, their hearts beating in rhythm with the land and the climate, with the very soil that they labor in. Deep within their culture is an identity with that soil, with its innate mystery and value, a sense of its holiness. Even a modest harvest is a great source of pride and a cause for celebration. As one chile farmer is quoted in Carmella Padilla’s The Chile Chronicles, “My mother always used to say, ‘If you plant it with joy, it will grow.’”

One day I was eating a late lunch after a night on call. Our attending was an older man who inhabited a wonderful, open hacienda style home outside of town in the foothills of Sandia Peak. At the end of each rotation, he would host his residents and students, introducing us to New Mexican wine as we looked over the lights of the city. He exuded calm, a trait much needed in those days, and one I have tried unsuccessfully to emulate in the years since. He walked onto the patio, bowl of stew in hand and sat down with me.

One of our admissions the previous night was a poor, elderly chile farmer from Chama, his large extended family having brought him all those miles for care at the VA. It was an impressive sight, this tribe of modest laborers all gathered as a family to stand vigil. He had told me about his little farm and his family that night and I related some of it on rounds. “I’ve always admired people like him,” my attending said. “When we are at our best, we are more like them than you might think, grounded in culture and family. When you leave here, you’ll take a new culture and a new family with you.” I’ve thought about that offhanded bit of wisdom dispensed over a bowl of green and have considered its meaning in the years since. Those chile farmers were deeply rooted in the soil, the rhythm of the seasons and their heritage. It binds them together, gives them purpose and faith. Along with my own heritage of faith and family that I brought to New Mexico, I added new roots, the timeless culture of medicine and healing, and had been given a new family, just as you were on your own unique path. That sense of culture and family, that calling, will always be there, waiting for us to return even when we wander or forget, drawing us back, in some form or another, to what we were meant to do.

Brian S. Sayers, M.D.

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Submitted September, 2021

by Dr. Michelle Owens

Gratitude

During a well-being debriefing with my work family this week, the strategy of practicing gratitude was shared as a way to practice self-care to be able to navigate these continued times of uncertainty and acute on chronic stress.

This resonated with me deeply as earlier in the year I had adopted a gratitude practice with my husband. Every evening, right before bed, we take turns sharing 3 good things that happened to us during the day. Often times they would be similar and related to our young children. We found it to be a nice way to end the day and drift off to sleep with comforting feelings instead of exhausting thoughts of one of the many worries or stresses of the day. I also noticed I slept deeper and was more rested in the mornings.

I’ve heard other colleagues share similar gratitude practices - some starting their days off by reflecting on 1 good or meaningful thing that happened the day before; others reflecting on 1 meaningful interaction they had with a patient or family that day on their drive home from work; and others practicing daily gratitude journaling. They all shared how impactful their gratitude practice had been on their overall well-being, and many shared that they look forward to that practice each day.

This is not a novel idea and the field of positive psychology has focused on the impacts of practicing gratitude with happiness for years. It’s not surprising that people who routinely incorporate the practice of gratitude in their lives report feeling happier, more optimistic and with an improved well-being. Some studies have shown increased exercise and fewer visits to physicians, as an association with the practice of gratitude.

There are many ways to practice gratitude and none are superior to others - it’s truly what speaks to you and ultimately fills your cup. Gratitude is a salve for our emotional wounds.

What ways do you incorporate the practice of gratitude in your life?

Dr. Michelle Owens

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted September 2021

By Mark Rosen, M.D.

Seeing the lost and overwhelmed look on one of the new ICU nurses reminded me of my internship.

My high grades came easy to me - until medical school. Suddenly I found myself surrounded by others at least as smart as me. Most of them had a hard work ethic while I was always able to manage without much studying. I continued to enjoy the campus and city life at my prestigious medical school, with grades well in the middle of the pack.

I applied to 13 top internship programs plus two safety nets. I got into #14. I was devastated. This was in Miami, Jackson Memorial Hospital, and some of the wards were not even air conditioned. I was so naïve back then. I had no idea that to get into a top internship, you needed to get references from top academicians, and you need to have done research for at least one of them. Not me.

My first month was ICU, where the resident just had one intern and I was protected for the most part. The second month was the Medicare ward, old and sick. My first night on call the ER doc admitted to me a patient with pulmonary edema. I went to the ER and saw a cachectic man on a Bird respirator (as if anyone reading this knows what that is), no edema, no rales. Bed, IV pole and ventilator. It was my responsibility to move him to the floor? How? Do I have to grow a third hand? You know us guys, we don’t like to ask for help or directions. But I had no choice. Turns out we were to call respiratory therapy and they move the vent. I got the patient tucked in upstairs and figured out he had decompensated COPD. Dry as a bone. My first big lesson: don’t trust what other doctors or the patient tells you about the diagnosis. It’s a good place to start but make your own decision.

Things went downhill from there. I was sure I would kill someone from missing an obvious diagnosis (we learned thousands of them in med school) or ordering the wrong medications (ditto). I became depressed with what I now recognize as PTSD. Couldn’t sleep, no appetite. Dreaded going to work. Tachycardia whenever I was not at work and heard a siren.

My medical school rotations, being at a tertiary referral center, gave me little chance to make decisions. I’d be the fourth or fifth doctor to see the patient, and everything was known and planned by that time.

I told my housestaff director that I was going to have to quit. He refused to accept this and told me to take some more time. I had an elective coming up and wouldn’t be faced with decisions or night call for a month. I saw a therapist. Wasn’t given antidepressants or antianxiety meds, not sure why. I sure needed them.

Month 4, back on general wards. Night call, asked to see one of my fellow intern’s patients with abdominal pain. He had a board like belly. First thought, call surgery. Second thought, he will ask me what does the CBC and abdominal film show? So I ordered those. Free air under the diaphragm, called surgery, off to repair a perforated peptic ulcer.

Even now I still tear up when I tell this story. I realized that I did know what I was doing. There were only a few medications for pneumonia, not thousands. There were only a few diagnoses we had to deal with daily. The few exceptions were sent to specialists, discussed in morning report or grand rounds, and got treated appropriately.

My symptoms resolved and I finished my training without further such problems.

In retrospect, I was thrown into the deep end without knowing how to swim. If I had been accepted at one of those top internships, I’d still be dog-paddling. I truly believe that I am a much better clinician now having had the training at Jackson Memorial rather than elsewhere.

Which is sort of the story of my life. Without exception every disaster, calamity, disappointment in my life has turned out to be the opening to something better. Sure, part of this is just my attitude about life. If I’m on vacation and miss a plane, so what? I’m still on vacation. Read a book in the airport instead of on the beach, who cares?

I met my wife of 47 years in Miami. Which wouldn’t have happened elsewhere obviously.

I’ve been practicing medicine for 44 years. From the start I’ve heard my colleagues complaining about how it’s not like the “good old days.” They would tell my son not to become a doctor. He didn’t heed that advice, and last week moved to Palo Alto to start an IBD research program at Stanford.

I prefer to look at the positive side. I love what I do and I’m good at it. I love my partners, who always want to help out. I love the hospital nursing and ancillary staff. They always seem happy to see me. I’m 74 years old but why would I retire? I’m having too much fun. Plus, every day there are at least one or two amazing patient stories that arise.

The practice of medicine will continue to change, for the good and bad. Accept the inevitable and learn to work with it. You will be much happier than if you fight it.

Mark Rosen, MD

mrosen@austinkidney.com

Submitted August, 2021

by Dr. Anna Vu-Wallace

No One Dies of COVID

“No one dies of COVID, right?” This was one of the first questions my patient asked me in our initial encounter. My immediate thought: “What??!!” He went on to say, “It’s just another virus, like the flu, I am told.” My response: “Who told you that? Where did you get your information?” Despite the calm exterior, I felt intensely angry. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to stay in anger long. Within hours, my patient was intubated. Even before he was intubated, he couldn’t believe he was heading into respiratory failure and needed a ventilator. The following days were struggles to keep his vitals and numbers stabilized. Some days we were successful, other days we were not. He died two weeks after his intubation.

I am certain many of my hospital colleagues encountered similar patients during these past 17 months. I heard sarcasm and anger from physicians and nurses, echoing my own internal attitude towards these patients. It had been building up to this point for me since the beginning of the pandemic. Like everyone, I had my fears when the pandemic started. In the beginning, there was so much support for those of us in the hospitals.

Then, it started to fade when misinformation surfaced. Anti-mask protestors appeared with subsequent bans on mask mandates. In a divided country, there was even more division on this point. The anti-vaccine movement seemed to end our patience the moment it started. I saw the outpouring of anger and disbelief from the medical community. By this time, it felt as if we were abandoned by the public. How can any of us not feel anger? We have every right to be. We are human, after all. Many have been overworked for years and were asked to give even more.

Staying in anger, disappointment, and negative emotions has had its effect. Fatigue and burnout settled in. Dr. Sarah Smiley, the leader of our hospital practice, defined the state as “…haggard and stressed,” in referring to all the nurses, therapists, doctors, chaplains, and hospital staff. “Even the greeters and security guards are weary,” she recalled.

My daily calls to families, much to my surprise, became a part of my healing. The personal calls led me to understand who my patients were and what led them to believe what they believed. These daily calls allowed me a look into the person, not the “annoying, ignorant patient” as judged by this physician, but a human whose life has been rich in gifts they gave to others. I realized, when I am in judgment, that it just takes knowing the other person, really knowing them, to understand and let go of judgment. I heard the sounds of their weeping and understood how much my patients’ lives touched those who knew them.

Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross said, in so many words, to truly serve altruistically, we must understand our own biases and let them go before entering a patient’s room. These phone calls were often the only thing I could give to families to comfort them. The calls were often the pause I needed to look at my own biases and judgment, and just listen. Surprisingly, anger and frustration softened. My practice partner, Dr. Pamela Cowper, said recently, “I thought that I would have little sympathy for these patients who were not vaccinated, but I found it to be the exact opposite. I am rooting for them all. I am sure I picked the right career.”

The pause and listen seems to be key. False perspectives from my patients do arise from some element of truth. My husband, a retired business executive, life coach, and minister, reminded me, “To be open to another perspective, a person needs to first feel validated in some way that her/his own perspective has merit on some level, too.” Married to a highly educated and non-medical person, my husband also reminded me that despite his graduate studies, he knows nothing of the medical world. He said, “I don’t even know what questions to ask! I wouldn’t know who to believe if I didn’t marry a doctor. How would the public know who to trust given all the information out there?” This is a really good point. When I first met David, he didn’t know the difference between generic and brand name meds. He didn’t even know he could ask for generic medications, just as I would be clueless in his area of expertise.

So, how do I serve during such a tumultuous time? How do I serve those I disagree with? Pausing, listening, acknowledging other perspectives, and respecting the other person provided a space for conversation that can lead to change and healing. I don’t deny my emotions when they arise. I feel them and try to express them in a more constructive way. My anger and reactivity has not changed anyone. There is so much negativity now that I am careful not to add to it. I certainly don’t want to stay in negativity. It has not served me nor anyone else so far. By pausing and truly listening, I can reach for understanding. I am still working on this. It is an art after all….this doctoring.

Dr. Anna Vu-Wallace

annavuwallace@gmail.com

Submitted August 22, 2021

by Dr. Michelle Owens

I Don’t Want to be Resilient

I went to replace four hanging plants at a nursery this past weekend because they all died once the Texas heat made its appearance, despite being watered, placed in the shade and talked to by my daughter and me.

While I was looking for plants that will hopefully survive the Texas summer, I was chatting with my husband who cheekily said, “those plants weren’t resilient.”

He of course knows my disdain for the word “resilient.” I have shared quite a few times this year why it makes me cringe so much. The term “resilient” has been thrown around so flippantly since COVID that it is a real buzzword now.

As I have told my husband before, I do not want to be resilient. Being resilient to me means you’ve survived a dumpster fire white knuckling the whole way through at the brink of death but then manage to come out on the other side, traumatized, but still alive. Some might describe their experiences with COVID this way.

I believe there are ways we can be more proactive to fend off having to be too resilient too often.

I challenged him and said, “I do not want resilient flowers, I want hearty flowers. In fact, I want to be hearty.”

A quick Google search provided me the Webster Dictionary definition of the two:

Hearty means “vigorous and cheerful”; “strong and healthy”; “wholesome and substantial.”

Resilient means “able to withstand or recover quickly from difficult conditions.”

Looking at the image search is even more telling - hearty images show wholesome stews and soups, while resilient images show a human figure pushing a boulder up a hill.

I would much rather have a solid, hearty foundation than a resilient one marred with cracks, chips, and unevenness.

I worry that many organizations think “resilience training” is the answer, that if we all had a little more training in resilience, we would all be better for it. Honestly, I think resilience training is counterintuitive, exhausting and a slap in the face to the person having to complete it. Retroactive resilience training when staff are already burned out just contributes further to their burnout and feelings of failure.

The need to provide resilience training suggests that our perceived lack of resilience is the core problem, that “if only you were more resilient, you’d be happier/less burnout/ etc.” Perhaps we and our lack of resilience really isn’t the problem?

We all know watching a module on resilience, sitting in a lecture about mindfulness, being told to practice more yoga and breathing techniques does not make you feel less burnout. It’s having the support and buy-in from your workplace, to actually have the time to do the things that feed your soul and fill your cup. Adding more onto an already overflowing plate of life’s stressors only makes it heavier and more overwhelming.

I want support. I want authentic connection and compassion. I want someone invested in my well-being who prioritizes my self-care to prevent me from having to be perpetually resilient. I want someone who values my heartiness and helps to cultivate an environment that fosters continued growth for myself and others.

Dr. Michelle Owens

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted August 15, 2021

by Dr. Christopher Chenault

My Journey in Medicine and Life

I have been reading Dr. Sayers’ articles on the TCMS Wellness Program page as it provides a window into other lives in this journey of medicine and life in general. We all start out on a road that would seem quite like other travelers in training and practice, but we all find a unique and special way of stepping over or around the rocks and pebbles on the way. Some of us find these obstacles more difficult to ignore or put behind us, leading to more worries.

I do not wish to be too pollyannaish, but I have found medicine to have been a wonderful world in which to participate. Of course, medical school was a difficult goal to achieve, but when I finally got there it was exciting and challenging. We all knew it would be hard work and it lived up to its reputation. But it was grand and full of excitement and wonder. I scrubbed with Dr. DeBakey and Dr. Cooley and survived, held the artery after arteriograms, resuscitated a cardiac patient on the floor with only the respiratory therapist, delivered a lot of babies, set a few fractures, and did all the same things that all of you have accomplished and loved it. It was one of the highlights of my life. Following internship and general surgery residency, I spent two years in the Indian Health Service where I learned cert ain patient care techniques that I used the rest of my years in practice. My orthopedic residency was very much to my liking and they actually introduced me to the practice in Austin that I eventually joined. I found the group a remarkably congenial, smart, honest, and talented lot with which to practice. You just can’t find a better way to spend your days. Yes, we were in the ER a lot. One internist did the numbers and found that the general surgeons were called to Brackenridge about 110 times per month and the orthopedist around 103 per month. That’s a lot! But we had good dedicated colleagues with whom we shared that responsibility. Sure, sometimes in the middle of the night I felt a bit lonely and isolated, but I could call for help if needed.

During my practice, I realized you couldn’t run a school without a good PTA and you can’t run a hospital without committees. So, I served on a few committees where I got to know some doctors in other areas of medicine. The credential committee at Brackenridge and later at Seton brought some real insight into the workings of other departments and the complexities of privileging certain specialties. That also allowed me to get to know some of the staff and administrators in both the hospitals and the Medical Society. The talent observed lifted my days.

A wonderful wife and family took me on many unexpected journeys to a myriad of horse shows, band trips, uncounted band concerts, family travels, PTA live auctions, and all the crazy things that families do. The horror was losing one of our children that became the low point of our lives. With support of partners, family, friends, and our church we survived and moved on. You never completely move away from that but with support it becomes tolerable.

I don’t know why I feel so lucky because I know that many others are blessed as much or more than we have been. The comparison doesn’t make any difference. It is the absolute of what we live that is the joy. The opportunity to make at least a few people feel better in their pain makes the trip worthwhile. And the companionship of community is a remarkable balm to help manage the bumps in the road.

I present this story as a person who has very much enjoyed medicine as a vocation in spite of some complications and in contrast to the more difficult paths others have encountered.

And retirement is pretty nice also.

Christopher “Kit” Chenault, MD

cchenault@austin.rr.com

Submitted August 2021

Three Trout and Wisdom from the Ordinary

Let’s be honest about something that people are notoriously dishonest about. Fishing. I am just a terrible fisherman. I’m no good at picking bait. I’m impatient. I try to set the hook too early or too late. I can’t read the water in a Colorado stream nor see redfish swirling in the bay. Some years back I decided to take up flyfishing after re-reading A River Runs Through It, thinking I might fare better. On a magnificent stream in Colorado, I managed to catch two nice trout one memorable afternoon, but I’d have to say the day ended in a draw because I also hooked my fishing hat twice. I feel pretty sure that my father-in-law, a great outdoorsman, went to his grave wondering why in the world his daughter married such a terrible fisherman.

With our adult children and six grandchildren recently in Port Aransas, I was determined to catch some fish with my eight-year-old grandson. There was a lake behind the house, and we fished it some that first day, but all we managed to catch was a very unfortunate turtle. I gave in and hired a guide for some bay fishing, but when we got to the dock that morning there was a message that he had called in sick. You don’t tell an eight-year-old that a fishing trip is called off, so on advice from a local in the bait shop we went to a spot where we could fish from a pier or wade. What followed was at once predictable and surprising. He caught a croaker, just a bit bigger than what we could buy at the bait store, but as I was about to throw it back, he wanted to look at it. He marveled at the different colors that glistened in the sunlight, the spines, the pumping gills. Over the next hour or so we caught three small trout, none of them keepers, but he was amazed at how slippery they were and laughed as they repeatedly squirmed from his grasp when he tried to throw them back. By mid-morning nothing was biting, but several dolphins joined us just a few feet away much to his amazement, and in the end fishing that I would have called a dismal failure was a great time that he talked about for days. It was only one of many times that week when ordinary things − collecting shells, letting their feet sink into sand in the surf, feeding seagulls − things I hardly notice anymore, fascinated them, and through them, became visible again to me.

The evening before we left, I snuck out to the lake at dusk to try my luck again. It was a still evening, a full moon rising, and the lake was smooth as glass. John Buchan famously wrote, “The charm of fishing is that it is the pursuit of what is elusive but attainable, a perpetual series of occasions for hope,” a quote that fits even unsuccessful fishing well, and life in general. The casts were well placed, or so I thought, the results predictable but soothing nonetheless and I stood there in the quiet of early evening, Norman Maclean style, in the half-light where, however briefly, “all existence fades to being with my soul…and the hope that a fish will rise.” Perhaps there is more fisherman in me than I thought, seeing the essence of fishing before me, even without fish. I stood there and considered the lessons of that week: that there is wisdom in the ordinary, and with each cast, hope.

Brian S. Sayers, M.D.

PWP Chair

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Submitted, July 2021

by Dr. Michelle Owens

A Heavy Load

I want to share a short story from Jon Muth’s book “Zen Shorts” titled “A Heavy Load.” I’ve read it to my daughter and this particular story really spoke to me.

“Two traveling monks reached a town where there was a young woman waiting to step out of her sedan chair. The rains had made deep puddles and she couldn’t step across without spoiling her silken robes. She stood there, looking very cross and impatient. She was scolding her attendants. They had nowhere to place the packages they held for her, so they couldn’t help her across the puddle.

The younger monk noticed the woman, said nothing, and walked by. The older monk quickly picked her up and put her on his back, transported her across the water, and put her down on the other side. She didn’t thank the older monk; she just shoved him out of the way and departed.

As they continued on their way, the young monk was brooding and preoccupied. After several hours, unable to hold his silence, he spoke out. “That woman back there was very selfish and rude, but you picked her up on your back and carried her! Then, she didn’t even thank you!”

“I set the woman down hours ago,” the older monk replied. “Why are you still carrying her?”

How many of you also struggle with holding onto things that don’t bring you joy, but rather rob you of it?

Life is too short to hold onto things that weigh you down without any potential benefit in sight. I know I have struggled with this from time to time.

Our time and energy are invaluable; we need to be good stewards of it. Much easier said than done - I know. We are so much better at offering this advice to our families and patients rather than taking it to heart ourselves.

What’s one thing you can set down this week?

Michelle Owens, DO

mowensdo@gmail.com

Editor’s note: Our guest writer this week is Dr. Michelle Owens. Dr. Owens is a hospice and palliative medicine physician, wife, mom, native Austinite, self-care advocate, and current scholar in the AAFP Leading Physician Well-being Program.

Brian Sayers, MD

Chair, Physician Wellness Program

bsayers@austin.rr.com

Submitted July 2021

I can’t carry everything.

Knowing our limits is so important - they are critical in guiding us to set, respect and implement healthy boundaries, which in turn fosters our ability for adequate self-care. Asking for help is also crucial - and much easier said than done.

I am amazed at the self-care practices my 3-year-old daughter already has. She inspires me. She names her emotions better than most adults. She reminds my husband and I to “take a deep breath and calm our body,” and has healthier boundaries than I have ever had.

I’d like to think that some of the language she has acquired has been from me. I’ve heard myself say - especially as of late - I can’t do everything. I have found it to be a validating mantra and almost daily affirmation that I am not superwoman, I am not immortal and I am human.

She often times tells me this phrase, “ I can’t carry everything” at bedtime when she is trying to carry her baby doll and 2 unicorns upstairs. I always carry the 2 unicorns after she has asked for help; she always thanks me. We both feel better- her load is lighter and I’ve helped her. Win. Win.

I wanted to share this with y’all as a gentle reminder to know your limits, set healthy boundaries, don’t be afraid to ask for help and to give you hope for the future generations. ❤️

Dr. Michelle Owens

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted June 2021

Shame, Empathy, Connection,

and the Sinking of the Essex

I just finished a book about the sinking of the Essex, an early ninetieth century whaler that sailed out of Nantucket only to sink after being attacked repeatedly by a huge whale on the open sea. Only a few survived after three months at sea in small lifeboats enduring exposure, thirst and cannibalism, eventually rescued 3000 miles away off the coast of Chile. The captain survived and returned to Nantucket; the fantastic story of the whale attack confirmed but still suspect. He went to sea once more, his next ship hitting a coral reef and sinking. No longer employable as a captain he lived out his days in obscurity as a night watchman. Herman Melville, who wrote Moby Dick based on these events, met the beached captain and remarked, "To the islanders he was a nobody. To me, the most impressive man, tho' w holly unassuming, even humble…" As I finished the book, I could only think of the shame he must have endured, and I wondered if anyone cared.

A decade ago, I heard Brene’ Brown speak at my daughter’s high school. It was before I was familiar with her work and a toddler on the row behind me kept kicking my chair, but a line from her talk did stick and I’ve thought about many times since, especially in interactions with physicians experiencing distress or addictive behavior. I couldn’t recall the exact wording until I came across it recently: “Everyone has a story or a struggle that will break your heart. And, if we’re really paying attention, most people have a story that will bring us to our knees.” For the most part, those struggles, often involving shame, are mostly hidden from view, even when carried by people we think we know pretty well, smoldering and informing their behavior and mental well-being.

While guilt is a sense that “I did something bad,” shame is a sense that “I am bad,” and Brown describes it as “the swampland of the soul.” When shame is unaddressed it can cause despair that fuels destructive behavior, addiction and a variety of mental health issues. Brown points out that shame expresses itself differently in men and women. In men shame stems from the fear of being perceived as weak, in women of failing to live up to the complex web of expectations society lays on them. Beyond that, physicians in general are susceptible to shame, born of subtle indoctrination in training and early career to deny imperfections.

Brown notes that “empathy is the antidote to shame.” Like shame, empathy is a hot topic these days and has as many definitions as it does researchers. A basic definition would be “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” Author Sherry Turke’s slightly different view is that it means, “I have a commitment to be there for you. I don’t know how you feel, but I am here to listen.” Empathy requires connections, and while for some the pandemic strengthened our closest relationships, for others close connections with a network of friends and family normally available with empathy were lost or badly fragmented. Over time, this loss of empathetic connections has taken its toll on many, the dramatic rise in utilization of our counseling program and physicians leaving medicine only t wo of many indicators.

While empathy refers to our ability to take the perspective of, and feel the emotions of another person, compassion is when those feelings and thoughts include the desire to help. Compassion is the action that (hopefully) results from empathy. As a society of colleagues, we are meant to look out for each other. Actively. In ways that the institutions we inhabit can’t or won’t, we check in, we give space for the people we work with and care about to confide, to connect. Research has repeatedly shown that half of our colleagues are in distress from work, if not their life around it, yet we can’t fully appreciate it unless we are face to face with someone who is suffering, and take the time to recognize it. As Mother Teresa once said, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will .”

Brian S. Sayers, MD