This page is an open forum for you to share your thoughts with colleagues.

Please consider submitting a brief blog with perspectives about our lives in medicine.

Blog anonymously with minimal descriptive information, or with your name.

Submit to pwp@TCMS.com

Submitted June 2025

by Tina Philip, DO

The Road Ahead

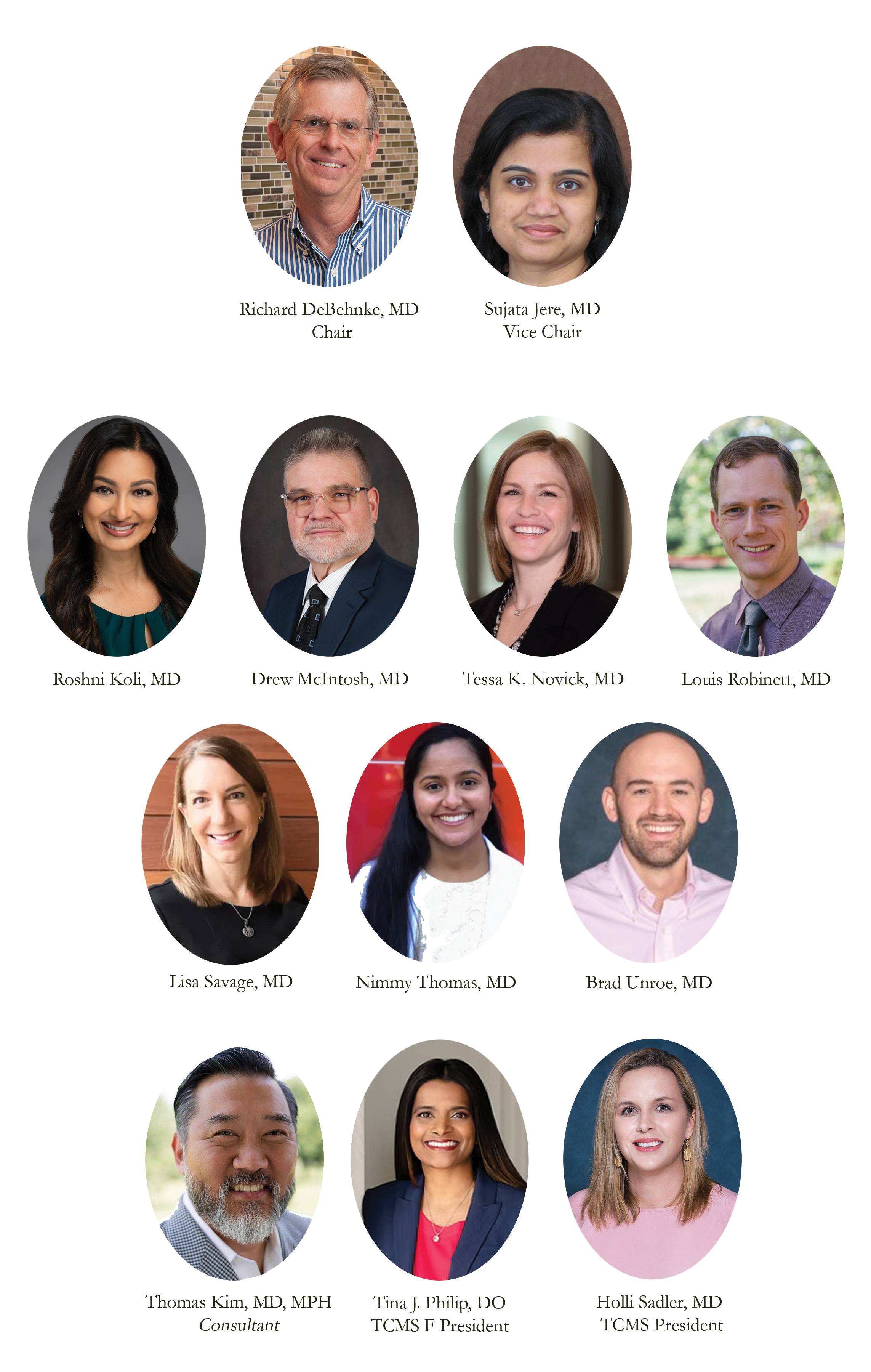

It is hard to believe that we have reached the halfway point of the year. As you are all aware, there have been many changes within the Physician Wellness Program (PWP). Since I last wrote to you, a dedicated task force made up of our physician colleagues set out to find the best way to move the PWP forward after the retirement of Dr. Brian Sayers as PWP Chair. The end result was the appointment of a new Steering Committee to provide insight, direction, and inspiration and the creation of a TCMS staff position dedicated to supporting the program. I would like to give thanks to task force members Drs. Richard DeBehnke, Lisa Savage, Louis Robinette, and Maria Monge for the time that they spent thoughtfully working together to create this plan and our TCMS Foundation board for their approval to move forward.

The Steering Committee met for the first time this past Wednesday and it was a productive evening understanding the origin and many facets of the program. The committee will be responsible for overseeing the Safe Harbor Counseling Program, weekly physician wellness blog, continuing medical education, and future program development. It was wonderful to see how the wealth of experience in this group, coupled with a strong commitment to physician well-being, will undoubtedly move the program into the future. I would like to thank Drs. Richard DeBehnke and Sujata Jere for stepping up to lead this committee as chair and vice-chair.

To provide support to the Steering Committee and ensure that the program has the resources needed, Michael Warburton was brought on earlier this month as Physician Wellness Program Manager. Michael previously worked with TCMS affiliate organization, We Are Blood, as the Volunteer and Grants Manager. With a bachelor’s degree in communications and a Master of Arts degree in Counseling, he has worked within the Austin nonprofit arena for over 25 years. He has already hit the ground running and brought so much valuable insight and creativity, and we are so glad to have him with us.

Although there have been many recent changes, the mission of the Physician Wellness Program remains the same: to support physician well-being and foster a culture where physicians feel valued, supported, and empowered to maintain their own health and balance while delivering exceptional care. This program is for our physician family and we can all play a role in making it a success. We love to hear the many voices of our community, so please contribute to the program by sharing a creative piece for our weekly blog and encouraging your colleagues to do so as well. The Physician Wellness Program also relies on the generosity of our donors, so consider making a monetary donation at the link below. Thank you to our physician members for your continued support. I look forward to seeing all that we can accomplish together.

PWP Steering Committee:

Dr. Tina Philip

tina.philip@gmail.com

Submitted June 2025

by Bob Emmick, MD

Carpe Diem

Everyone knows what free advice is worth these days, but I will attempt to offer something valuable in 600 words or less. First though, I must admit that we are privileged to practice the best profession in the world, in my opinion, and if someone has reached the point that they absolutely dread getting out of bed and going in to see their patients, I would seriously recommend professional help, changing professions, or retiring. People can debate whether we should feel joy in our profession, but satisfaction in listening to and helping our patients I believe is attainable every day.

Here is my advice. It is useful to have goals, but we should experience life to its fullest both in our profession and when we are at leisure, recharging our batteries. I will focus on the leisure side of life when we are seeking peace and joy, that period of recharging, but the thought process can be applied to our professional lives as well. I do not believe in the concept of bucket lists, nor the use of rankings that one thing is better than all others. Instead, I believe that life is to be experienced to its fullest and that each experience can be appreciated for what it offers.

As I understand it, the concept of the “bucket list” is to experience something once then check it off before moving onto the next experience on said list. There is a basic flaw in this, in that no two experiences of the same thing are alike. As an example, I would suggest the eruption of “Old Faithful” in Yellowstone. You cannot compare watching Old Faithful at sunset, in the middle of winter with snow covering the base, or late at night with stars and the moon in the background when no one else is around. A second example slightly to the south of Old Faithful is sunrise at Oxbow Bend in the Grand Tetons. Is it best seen in the spring when you may have a bear or moose swimming across the Snake River, or in the fall when the leaves have changed their color? I dislike the “one and done” approach because you have deprived yourself of the other opportunities. Seek out the experience and appreciate what it offers, multiple times if possible.

Focus on appreciating the experiences and not trying to rank them in order of the best and those that follow behind. During my first year of medical school a group of us went to Cozumel on Christmas break. There we went to dinner at Carlos and Charlies. On the wall was a set of “Rules.” I do not remember the others, but I will not forget the first. It said,”1. You are on vacation so eat something that you do not eat at home.” That has stuck with me, and I have expanded it into the concept of not ranking experiences but trying to savor as many as possible. Should you try to rank the best meal or trip or sunrise or sunset that you have experienced? Can they be ranked, and if so, why? I suggest that we should seek out the experience and enjoy it for what it is. Then savor the memory that will recharge your batteries in the future, not whether it was a check on your “bucket list” or number 1.

I hope that this perspective has helped someone other than myself. In the end it can be summed up in just two words, Carpe Diem!

Dr. Bob Emmick

remmick1963@yahoo.com

Submitted June 2025

by Louis Robinett, MD

Sunsets and Sonship

In April of this year, my wife, 15-month-old son, and I took a trip to the East Coast for a long weekend to visit friends. This was my son’s first flight in a while, and I recognized that this might be a special moment for us. He held my finger while we walked around the terminal, quickly finding a window with a great view of parked and taxiing airplanes with the assortment of utility vehicles that serve them. He must have stared out for 15 minutes – an eternity for a toddler – watching the busy workers, tiny carts, and giant airplanes zip back and forth on the tarmac.

When we boarded our flight, I was sure to pick a window seat for us, and my wife snapped this photograph of our view after takeoff – sharp, ruffled edges of a large cloud brilliantly illuminated by the setting sun behind it. I remembered my first memories of flying, my own father doing the same thing to make sure that I had a front-row seat to the same spectacle.

But what does this beauty mean to a 15-month-old? My son has so far lived an innocent, healthy life devoid of major trauma or chronic health issues. Though many circumstances are beyond my control, it is among the greatest privileges as a father to provide stability and safety as my son grows and develops. Right now, he knows that the stove makes tasty food, but not that it can burn him. He knows that playing with the garden hose in our backyard is his favorite thing, but not that it’s contingent on next month’s mortgage payment. And I don’t want him to know that the plane he is in might crash, or that the ticket was expensive – I just want him to experience the wonder of viewing a sunset from 30,000 feet. The joys are for today, the burdens for another time.

I moved my face next to my son’s in the window because I, too, wanted to take in the weight of this moment. In the days leading up to our vacation, I was burdened with thoughts of my practice, my finances, my marriage, the hours of sleep I didn’t get the night before, my patients, not to mention the pile of notes that I brought with me from the week prior. What does this sunset mean to me, a middle-aged physician and father? Gazing at the magnificent scene, I couldn’t help but feel that all these difficulties were less important compared to the greater beauty that I was witnessing.

Maybe there are burdens that I, too, am being spared for now, ones that are for the future and not for today. I’m old enough to know that the stove can burn me and that my practice can financially fail. But there are also many more mistakes to make or mishaps to suffer in my lifetime that I have yet to experience, many that I never will. Tomorrow morning, the sun will rise again. Dew will be on the grass, bright red cardinals will roost in my red oak tree, the sky will be blue, and a breeze will occasionally ring my wind chime. Friends and family will still joyfully pick up the phone when I text or call. Spring will follow winter. Morning will follow night. Joy will follow despair. The brilliant cloud commands my attention to this.

And as I gaze back to my left, my son’s feet against my legs while he rests his head in his mother’s lap, I am filled with gratitude and thankfulness. I will carry these burdens with joy and grace. For today, the sunset is enough.

Perhaps, a humbling display of love from a caring Father.

Louis Robinett, MD

lrobinett@rheumtx.com

Submitted June 2025

by Lee Frierson-Stroud, MD

Music-the Soul’s Healer

We have been immersed in the rhythm of life from our very conception. Before we had nerves, ears, lungs—the rhythm of our mothers’ hearts surrounded us, accompanying us on the everyday adventure of becoming human. The lucky were exposed to music in utero. Music served as the soundtrack of our lives. Music is joy and sadness, humble and sublime, solitary and communal. Music is life itself.

Music is also healing. It is a source of endorphins—the good, natural, healthy kind. It is exercise—mental, physical and social. And, it is a gift to oneself, to one’s family and to one’s community.

Many, while growing up, sang or played in school/church choirs or bands. Some learned one-on-one with the piano, guitar, or other instruments. Others hummed and sang to themselves in the car and/or the wonderful acoustics of the shower. Mostly this was placed on the backburner in medical school and residency. We went in hearing one style of music and came out hearing something else. I went in to rock and roll and easy listening and came out to gangster rap and grunge. An elder physician missed the music I grew up to like “Top of the World,” and “Homeward Bound.” But, the call of music was still there.

The joy of music is crucial as one of many ways for physicians to deal with stress. In recognition of this, the Docs’ Noteworthy Ensemble was created. It was the only community choir active during COVID and the only Physicians Wellness Program to remain active in that incredibly stressful time for our physician community. Choral music of all kinds, some sublime (“Ave Verum Corpus”), some just fun (“The Lion Sleeps Tonight”) are featured. Participants are able to rehearse as their schedule permits. Phone calls from patients and colleagues during rehearsal are taken in stride. The idea is to relax as you can. We give back with two concerts per music set—one public with YouTube livestream and one at a nursing home. The archived livestream is available to share with shut ins. We have three concerts (Spring, Fall, and Christmas) per year to keep the music fresh and challenging. The ensemble is made up of singers and instrumentalists.

The audiences are touched by the healing sounds of music and the communal process. The sharing of the gift of music is basic to the human existence.

Thus, whether you love to sing or play music in an ensemble setting, are looking for something to do with one or more members of your family, want to support your musical family member, or if you simply want to go enjoy great live music, come enjoy the Docs’ Noteworthy Ensemble. Our next concert is June 28 at 2:30 pm at the Church at Highland Park, 5206 Balcones Drive (2222/Northland). If you are interested in joining our group or just learning more, contact me at 737-291-3048 or lfsim@me.com. Come join us as we share in the healing rhythm of life.

Lee Frierson-Stroud, MD

lfsim@me.com

Submitted June 2025

by Dr. Sumana Kumarappa, MD

Dancing Through the Demands

A Gastroenterologist’s Perspective on Wellness, Joy, and Preventing Burnout

As physicians, we live and work in high-stakes environments—where our time, energy, and emotional reserves are constantly stretched. Like many of you, I entered medicine out of a deep sense of purpose. As a gastroenterologist, I find meaning in every patient interaction, every procedure, every moment of healing. But over time, I began to feel what many of us eventually do: the quiet creep of burnout.

There were days when I felt like I was just moving through the motions—efficient, focused, but disconnected from joy. The emotional toll was subtle but persistent. I’d come home physically drained, mentally foggy, and somehow still thinking about patients long after I left the hospital. It made me realize something had to change. I needed something that filled me back up.

And I found it through dance.

Dance has always been a part of my life, but recently, it has evolved into something more than a hobby. It’s become therapy, expression, and joy—all rolled into one. What makes it even more special is that I share it with my daughter. We don’t just dance in the living room—though we love those spontaneous sessions—we also perform together with dance teams, rehearse regularly, and even film creative dance videos. It’s become a shared rhythm, a beautiful bond that keeps us both grounded.

In those moments, I’m not “Dr. so-and-so.” I’m not thinking about consults, lab results, or my inbox. I’m fully present—with my daughter, with the music, with myself. That space we create through dance has become sacred. It’s where I find energy again. It’s where I remember who I am outside of my professional role.

These moments are not just fun—they’re deeply restorative. After a week of complex procedures and emotional cases, a few hours of dancing can bring me back to myself. It reminds me that wellness isn’t about escaping the work, but about finding something that fills you up alongside it.

Sharing this joy with my daughter has been especially meaningful. She sees that her mom can care deeply for patients and carve out time for creative passion. She sees that joy and discipline don’t have to be separate. We learn from each other—she brings spontaneity, I bring structure, and together we create something that feeds both our souls.

This connection to dance has made me a better physician. When I take care of myself, I show up more fully for others. I’m more present, more empathetic, and more attuned to my patients. It’s a reminder that we can't pour from an empty cup. Physician wellness isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity.

I know how easy it is to push self-care to the side. We delay hobbies, postpone rest, and convince ourselves we’ll get to it “after the next shift,” “once this stretch is over,” or “when things slow down.” But things rarely slow down. And we don’t need to earn joy—we need to claim it.

Wellness doesn’t have to mean taking weeks off or making drastic life changes. It can be small, meaningful investments in the things that light you up. Whether it’s painting, hiking, writing, or dancing—find the rhythm that brings you back to yourself. And make space for it, unapologetically.

We hear a lot about work-life balance, but I’ve started to think of it more as life rhythm. Dance gave me that rhythm—something steady and joyful to return to. It’s not about balancing everything perfectly. It’s about creating space for things that matter outside of medicine so we can keep thriving within it.

To my fellow physicians: if you’re feeling stretched thin, I see you. If you’re running on fumes, I’ve been there. You deserve to feel whole—not just as a caregiver, but as a human being. Find what recharges you, and don’t let go of it. That thing—your joy, your creative outlet, your passion—is not a distraction. It’s your medicine.

For me, wellness looks like spinning under stage lights, filming a dance video with my daughter, and remembering that I’m more than my white coat. And that joy? That joy is what sustains the healer.

Sumana Kumarappa, MD

Austin Gastroenterology

sumana.kumarappa@austingastro.com

Submitted May 2025

by Dr. Shangir Siddique

Spring Cleaning Your Roles and Responsibilities

With the coming of a new year, we always have a chance to reflect on what worked and didn’t work in the previous year. In addition to finally cleaning up the mess I ignored while working over the holidays (the hospital never sleeps!), I take a moment to take inventory of something equally important as a clean environment: my obligations and responsibilities. Like many of you, I pride myself on being active in my local medical community and part of the Texas Medical Association. Oftentimes, I’ll take on additional roles and responsibilities outside of my work as a physician, or in organized medicine. It’s easy to forget how you only have 24 hours in a day when during residency, you would often spend most of your waking hours taking care of patients. However, I noticed that it is very easy to have a schedule filled with different meetings, working groups, projects, and roles/responsibilities that individually seem like great ideas, but overall take away from the time I have to myself.

In these fleeting days of spring, take a minute to jot down all of your ongoing obligations, professional, and not professional. Some things are extremely difficult to prioritize as being more important than others but try your best to rank these priorities and obligations from most important to least important. One way to frame “importance” is the impact it has on your well-being. Not only do I consider my work in the TMA objectively important, but I derive a subjective feeling of accomplishment and hard work when I work on a resolution that makes it through the House of Delegates or coordinates with colleagues across the state for ongoing medical issues. To keep it simple, sometimes the work can feel like it’s not work. Prioritize these activities and allow yourself to engage in communities/efforts that bring you a sense of accomplishment and meaning. However, if you find things on that list that don’t provide a sense of accomplishment, don’t provide that sense of impact, or worse, become a negative stressor that isn’t leading to personal/professional growth, ask yourself if you would like to continue to dedicate your limited time and energy towards that effort.

It’s always hard saying no, especially for those of us who entered a field dedicated to healing and serving others. Your impact as a physician will be far greater if you prevent burnout and have a longer career, rather than being overly passionate and stretching yourself too early on and then retiring sooner than you would hope. When transitioning out of a role, I suggest recommending an appropriate replacement if needed. Depending on your role/organization, this may allow for a positive career trajectory for that person, while also establishing yourself as a team player who wants the overall team to succeed.

Taking this approach has allowed me to focus on being effective and efficient with my roles and responsibilities, while also nurturing a strong network of colleagues who I can always reach out to for their advice and perspective. I hope this spring brings you much growth and abundance!

Shangir Siddique, MD

ssiddiquemdmph@gmail.com

Submitted May 2025

by Dr. Michelle Owens-Kumar

A Moment’s Grace: Navigating Medicine & Motherhood

Being a physician mom is a juggling act like no other. I knew it would be hard, but I never imagined just how much. The guilt, the exhaustion, the constant pull between caring for patients, leading teams, and showing up fully for my children—it’s overwhelming. And yet, in the chaos, I’ve learned one of the most valuable lessons: give yourself grace.

Before motherhood, I thought my medical training in family medicine would prepare me for parenting. I couldn’t have been more wrong. From the struggles of childbirth and breastfeeding to the brutal reality of functioning on minimal sleep, I pushed through, often too hard. Looking back, I wish I had been kinder to myself. I wish I had whispered, It’s okay. Ask for help. Take a break. The notes can wait. You are doing an amazing job.

Now, I try to be more mindful of my inner critic, to set and hold boundaries, and to remind my colleagues to give themselves the same compassion they so readily give to others. I’m far from perfect, but I’ve grown. And when I struggle, I ask myself: What would I tell my daughter if she were in my shoes? The answer is always gentler, always more forgiving.

The other day, my 6-year old daughter told me that when she grows up, she wants to be a veterinarian, an artist, and a mommy. Then she looked at me with wide, curious eyes and asked, “But mommy, how do I do all those things at once?” I had never felt so seen. I paused, unsure of the perfect answer, and said gently, “You do the best you can in each one, knowing you have to take time for each—and be kind to yourself, because you can’t do everything at the same time.”

Recently, I chatted with a colleague, and we shared how there is so much overlap between our personal and professional lives as mothers, doctors, and leaders. Our doctoring shapes our mothering, our mothering strengthens our leadership, and our leadership informs it all. But too often, we forget the grace we need across all three roles.

I wonder what it would be like if we scheduled moments of self-kindness each day. What if we paused long enough to honor all we’re doing instead of focusing on what we’re not? What if we allowed ourselves, just for a moment, to step away from the hustle and simply be—without guilt or expectation, and just with grace?

As we strive to be well-models for the next generation, I hope we also remember to extend that same kindness to ourselves. You are doing enough. You are enough. Give yourself that grace.

Michelle Owens-Kumar, DO

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted May 2025

by Natalie Malluru

The Unseen

In sterile rooms where echoes swell,

Between the charts, the notes, the tell

A quiet battle, buried deep,

Where shadows lurk, and secrets keep.

What weighs upon the hands that heal,

When pain is real but stays concealed?

A spectrum cast in muted tones,

Yet thrumming loud in weary bones.

Each breath of anguish, thin as air,

Felt so sharp, yet never there.

In jaded eyes, a fleeting fear

Will my truth be lost, unheard, unclear?

This world of science breaks and mends,

It measures wounds, yet not the bends

Of spirit twisted, pulled too tight,

A silent war still out of sight

But look beyond what scans reveal,

Beyond the proof, beyond the steel.

See the weight, the quiet ache,

The fight they fight but cannot break.

So fear not the edges, let them blossom and grow,

Each thread of existence is vital to show,

In this clinic of hearts, understand what they bear,

Dissolve doubt that lingers, and breathe in their air.

Together we navigate this invisible tide,

Charting paths of resilience, with you here beside,

In the fabric of healing, let patience be bright,

Let us honor the pain, transform darkness to light.

Author’s Note

"The Unseen" depicts the challenges encountered by individuals suffering from invisible illnesses, such as fibromyalgia - a complex condition that is often overlooked or misunderstood. It captures the internal struggle of patients whose suffering is real yet elusive in the eyes of modern medicine. The lines convey a sense of isolation as patients battle not just the physical aspects of their illness but also the pressure to prove their pain. These writings stem from wanting to honor the unseen and are inspired by my time rotating through fibromyalgia clinic.

Natalie Malluru | MD Candidate, Class of 2025

nataliemalluru@utexas.edu

Submitted April 2025

by Robina Poonawala, MD

WHAT IS HAPPINESS, REALLY?

Happiness is the elusive butterfly we all chase, hoping it will land on our shoulder someday.

But what is happiness, really? Is it a feeling, a destination, a skill or a state of mind? Does it come from fancy titles or free time?

The modern workplace is designed for efficiency, not joy. The employees are given targets, not indexes for happiness. Imagine a world where companies offered “happiness bonuses” instead of “performance bonuses.”

Psychologists say happiness is 50% genetics,10% circumstance and 40% mindset. So, if you were born into a family of worriers, you are halfway to anxiety. The remaining 50%? Well, that is where the magic lies.

Social media has redefined happiness. A vacation is no longer about relaxation but about curated Instagram posts. The pressure to appear happy has taken over the need to be happy. And let’s not forget about consumerism’s goal in happiness. Advertisers have convinced us that happiness can be bought - the right car, the right watch, the right perfume. But as the saying goes, ‘money cannot buy happiness,’ but it can sure buy a yacht, private jet, or a thing or two.

Neuroscience tells us that small joys release dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin–the holy trinity of happiness. It’s why a Frappuccino, a dog’s wagging tail, or a smile can brighten your day. A smile can trigger another smile, creating a ripple effect.

We often forget that happiness and health are two sides of the same coin. You can have all the wealth in the world, but if your back cracks louder than your most comfortable chair, joy feels distant. A balanced life is not about financial success, but physical and mental well-being too.

The irony is we spend our youth chasing money at the cost of heath, only to spend that money later trying to regain it. We treat happiness like a pension plan, deferring it for later, believing things like, “I’ll be happy when I get a promotion,” or “I’ll be happy when I buy that dream house.”

But happiness does not come gift wrapped with a milestone. Happiness is not a future event; it’s a present choice.

The key criteria for happiness generally include financial stability, strong relationships, good health, and a sense of purpose. Money can provide happiness by providing basic needs and security but beyond a certain income level, additional wealth has little impact on long term happiness. More important are strong personal connections–family, friendships, and community. Good physical and mental health play a significant impact on happiness as does having a sense of purpose whether through work, personal growth, or helping others.

Ask a child what makes them happy and the answer will be simple; an ice cream cone or picking up seashells on a beach. Ask an adult and the answer will be a complicated mix of ambitions, financial stability, and societal expectations. Somewhere along the way we stopped living in the moment and started living for the future.

In summary, let's recognize that happiness is not a luxury, it’s a necessity. It is not found in grand achievements but in small, everyday moments. True success does not lie in reaching milestones but in savoring the journey. A world that prioritizes happiness is a world that thrives, and perhaps the real measure of success is not how much we have accumulated, but how much joy we have created–for ourselves and those around us.

Robina Poonawala, MD

robina.poonawala@gmail.com

Submitted March 2025

by Louis Robinett, MD

Is this it?

A couple of years ago, an acquaintance of mine from medical school posted a series of concerning posts on his Facebook profile. I reached out via Messenger, and we had a brief conversation that revealed he was not doing well. He had just completed extensive post-graduate training as a surgical subspecialist. He had a beautiful family, and he bought a lovely home in the town where he settled as a respected member of the medical community. From a career standpoint, he had finally made it. So how in the world could someone in his position be depressed? It seemed that he was wondering the same thing.

I have witnessed this pattern in a number of friends and patients, and while the process may differ for each, the result is the same. A physician finally makes partner, a young professional lands that coveted job at a flashy company, a stay-at-home mom’s children finally leave the house and she finds herself at loose ends. After years of labor, you finally achieve your goal, and yet find yourself asking the question:

Is this it?

I recently saw a Reel of an interview of Jason Alexander, the actor who played George Costanza in Seinfeld. He told a story of finally winning a Golden Globe award after a lengthy career of hard work. Despite how incredible the moment was when given such a great honor, when the ceremony and after-party were over he got back to his hotel room and found himself surprisingly disappointed. “Is this what it feels like to be at the top?” he thought. He wished he had taken the time to enjoy the process and had a more realistic expectation of the destination.

There are similar realities in the field of medicine. I was struck early in my career how much the day-to-day work of a doctor felt more like a normal job than the fulfilling ministry I had envisioned in my pre-med days. Our patients commonly have the same mindset, treating our interactions with them as a transaction, not appreciating the weight of responsibility and beneficence we feel for them. Much like the story of Jesus healing the ten people with leprosy, only one came back to say, “Thank you.”

Being no stranger to these feelings myself, on bad days I feel like clinical practice does little more than just punch my paycheck. But I have to remind myself that this is only a portion of the totality of work that I do. No vocation is absent of frustrations or repetitive tasks, and I must accept those along with the joys and rewards that come with them. It is also important to remain thankful in all circumstances – our human nature naturally focuses on problems and suffering instead of realizing gratitude. I have a recurring monthly email I schedule to myself to remind me to, “Be thankful for both the blessings and challenges of this season.” I started this a year ago during a particularly stressful time at my practice. And finally, according to my Christian worldview, I try to remember that my identity ultimately lies with God’s perspective of me, which is independent of performance, successes, or failures – a concept that I all-too-easily forget.

From one physician to another – thank you for what you do. Remember that all our work is meaningful, even when we feel like it isn’t. Each mundane task (does anyone enjoy writing notes?), challenging diagnosis, and successful treatment helps to improve the health and lives of our patients. If indeed, ‘this is it,’ be encouraged that you are making a difference in the lives of others and know your colleagues (and even your patients) see your worth and value.

Louis Robinett, MD

lrobinett@rheumtx.com

Submitted March 2025

by Michelle Owens-Kumar, DO

Sing Sweet Nightingale: What a Lullaby Teaches Us About Physician Well-Being

As I sing this song at bedtime to my youngest, I wonder what about this song, in particular, is so comforting to him. Is it the melody, the familiar voice, or the cadence of the words? Did watching Cinderella with his older sister really leave this strong of an impression?

As I thought of it more and researched the meaning behind it for myself, I was pleasantly surprised to find that this song has often been viewed as a beautiful escape for Cinderella from her unfortunate circumstances—an attempt to preserve her mental well-being despite the adversity she faced.

In fact, the nightingale has often been seen as a symbol of strength, hope, and healing. In literature and mythology, the nightingale’s song has long been associated with solace in times of sorrow, a reminder that beauty and light can exist even in the darkest moments. For physicians, who often bear the emotional and physical toll of their profession, this symbolism is particularly poignant.

Much like Cinderella seeking refuge in her song, many healthcare professionals turn to moments of reflection, music, or personal rituals to maintain their well-being amidst the demands of their work. The nightingale, often a metaphor for endurance and renewal, reminds us that tending to our own mental health is not just necessary but vital in sustaining our ability to care for others.

But beyond just seeking comfort, we must also recognize the importance of channeling our inner strength during difficult times. Struggle is inevitable in medicine and in life, but unnecessary suffering comes when we resist what we cannot control or when we neglect to replenish ourselves. True resilience is not about enduring hardship in silence—it is about knowing when to pause, when to seek support, and when to lean into practices that nourish us rather than deplete us.

I find myself reflecting on the ways in which we, as physicians, can create our own moments of respite—whether through music, mindfulness, or simple acts of self-care. Just as the nightingale’s song provided Cinderella with a sense of peace, we too must find our own melodies that sustain us, allowing us to navigate the challenges of our profession with grace. In doing so, we not only protect our well-being but also ensure that we can continue to show up fully for our patients, our loved ones, and ourselves.

Michelle Owens-Kumar, DO

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted March 2025

by Scott Clitheroe, MD

A Kind Gesture

In 1990, on the internal medicine wards at Hermann Hospital in

Houston, Texas, it was (morbidly) joked that there were three types of

inpatients: those with AIDS, those with tuberculosis, and those with both.

It was to these wards that I was assigned as a third-year

medical student on my internal medicine rotation. I was nervous. The patients

with AIDS were numerous and very sick. The medical student duties included

drawing blood cultures on patients that spiked fevers. Needle sticks were a

constant concern to us novice phlebotomists.

Early one evening, my supervising resident told me to draw blood

cultures on a patient who was spiking a high fever. He was a middle-aged

Haitian immigrant admitted with AIDS-related Pneumocystis pneumonia. Despite

appropriate treatment, he continued to spike fevers, so blood cultures were

ordered.

When I entered the room, wearing my mask and isolation gown, I

was met with a kind smile from a gaunt man. I introduced myself and told him

that I needed to draw blood from both arms. Like a supplicant, he outstretched

both his arms and said I could join the crowd of vampires.

I perspired under the heavy gown. I also was hungry and probably

hypoglycemic, as I hadn’t had time to eat lunch or dinner. I guess I looked

peaked, because as I was preparing to draw the blood, he asked me if I was

feeling okay.

Taken aback by the question, I murmured something about being

hungry because I had skipped lunch. I didn’t want him to think I was nervous

about the procedure. He replied that I shouldn’t be skipping meals, because

learning was harder on an empty stomach. I nodded in agreement, finished the

blood draws, thanked him, and left the room.

The next morning on rounds, one of the ward’s nurses told me

that the patient asked to see me. I had not been assigned to his case; I had

just been there to draw blood. So, I was confused as to why he would want to

see me.

When I entered the room, he motioned me over to the bed and the

bedside table, where his breakfast sat uneaten. On it was a wrapped muffin and

a ten-dollar bill. He insisted that I take the snack and the money. He had

assumed that the reason I had skipped meals was not due to lack of time, but

lack of funds. I was blown away by the generosity of a man, dying alone in a

foreign country, who was still able to think of others’ needs.

I thanked him and tried to correct his assumption, but he

insisted. Finally, I acquiesced and took the muffin and the ten-dollar bill and

left the room. That muffin tasted really good, and I used the ten-dollar gift

for both lunch and dinner that day.

I stopped by his room the next day to thank him. He clearly was

not feeling well but he managed a smile and a few kind words. I never saw him

again. He passed away a few weeks later.

When I am feeling stressed, sad, or scared, I often recall the

kind gestures of a dying patient and remember that the best remedy to these

common human emotions is to serve others. In that service, we can begin to

realize that the travails we encounter are not ours alone; that we humans are

all in this together.

What a blessing it is that we chose a profession where we are

privileged to be in service to others every day.

Scott Clitheroe, MD

sc51806@gmail.com

Submitted March 2025

by David Fleeger, MD

Just Get Away

I’m not exactly the poster child for work-life balance. So, when asked to post some musings about handling the inherent stresses of our profession I was a little suspicious they were going to use me to demonstrate what not to do. After all, our Travis County Medical Society already does a sterling job in providing resources to our physicians and their families who feel overwhelmed in their daily lives. If you feel in need of these services, your colleagues, friends, family and coworkers ask that you take advantage of the TCMS Physician Wellness Program counseling sessions. We want you whole and healthy.

Having worn a few hats in my medical career I have certainly seen my fair share of highs and lows, both in day-to-day patient care and in the political machinations faced by our profession. And like most, I have been helped through these days by my faith, family, friends, and coworkers. The pearl that I could pass along to my fellow physicians is to just get away. Both mentally and physically – just get away. For me, that means often combining two passions: photography and travel.

Photography has been an interest since residency, but it wasn’t until I entered practice that I began to seriously study, upgrade my equipment, and practice, practice, practice. I think the surgeon in me appreciates the technical aspects of the art and the ability to achieve a sharp and properly exposed image in an endless variety of circumstances. At the same time, the artistic side of photography is the most challenging. It’s not just a matter of good subject, light, and composition. It’s being able to use these to tell a story, to move someone – to capture a moment that has that ‘wow’ factor. This is the aspect of photography that you can work on for a lifetime and always have room for improvement.

The other passion that I share with my wife Jamie, is for travel. Although we have had many great trips within the USA, we decided early on (in our more mobile years) to get as far away as possible. I enjoy reading about the history and culture of an intended visit, as well as the geography, wildlife, and (of course) the photographic opportunities. Although travel these days can be a little stressful, we have learned to do our best to prepare and then just take things as the come. We did spend a Christmas in New Zealand without our luggage, but this gave us an excuse to buy a bunch of new clothes. Once in the country we try to immerse ourselves in the culture and experiences of the day-to-day lives of the locals. We prefer local guides and stay in locally owned hotels when possible. With a smile on my face and camera in hand I have met Buddhist monks in Bhutan, retired nuclear physicists in Cuba, and an Orthodox Christian priest named Paul in Patmos. For me the perfect location has no cell service and shoddy internet. I don’t bring any work with me. If I am doing it right, I don’t even think about work after two or three days. I will get my head back in the game and clear my emails out during layovers on the way back.

The combination of a technical skill that requires significant focus and the excitement of a strange and wonderful environment allows me to clear my head, forget about work, and create lasting memories with family and friends. The point is to both mentally and physically go somewhere entirely different from home. I know I have succeeded if when I get back to the office, I can’t remember my EMR password. So do yourself a favor and just get away.

David Fleeger, MD

davidfleegermd@austin.rr.com

Join me on Facebook for my Photo of The Day, click here

Submitted March 2025

by David Fleeger, MD

Submitted March 2025

by Dr. Christopher Parker

Doctoring and Learning: The First 25+ Years

July 1, 1997 was one of the best days of my life because I became a rheumatologist. I love caring for patients with multisystem autoimmune and crystal illnesses. Most of the time I am doing the teaching and coaching, however as a lifelong learner, staying abreast in medicine is always a massive challenge. I have always found it delightfully valuable to learn from my patients. Learning from patients often diminishes my stress regarding things like wrestling with insurance and other administrative hassles.

Here are a few keys to health and happiness my patients have taught me in their words:

1. From the late 70s guy who rides his motorcycle more than 100 miles to me once a year to refill his gout medication and Viagra. The keys to good health are, "Grow old but not up" and "try to eat less and have sex more".

2. From a 90s-year-old man I followed for decades with rheumatoid arthritis who always had a smile, even on the day after his daughter passed away from breast cancer: "I am so lucky to have known her for 44 years."

3. From a 60s-year-old lady who had very refractory rheumatoid arthritis: "I just need to laugh or cry, so I’d rather laugh." She would muster a smile and giggle. I would tell her that if I were her, I would sing the blues. She would often giggle again and say something like, "Then I

would cry since I'll bet you can't sing" and then we would both laugh.

4. From Freddie, a 90-year-old who I took care of for at least 20 years: "Always have the kind of job you would want to do in retirement."

5. From my patient's husband who came to see me in clinic a year after her death carrying a framed picture of her when she was a young lady: He wanted me to know that in her younger years she was very beautiful compared to the last few when I knew her. Then he pulled

out the letter of condolence which I wrote right after her death. He had been carrying it around in his wallet all of this time and wanted me to know "this meant a lot to me." It still chokes me up when I think about it.

Yes, there are words of wisdom here, but I find the true joy of medicine is within human connections and sharing whatever we can to lighten the burden of the human condition.

Dr. Christopher Parker

dr.positiveparker@gmail.com

Submitted February 2025

by Dr. Michelle Owens-Kumar

The Amen Effect: Honoring Our Own Suffering to Heal the Healer

In medicine, we bear witness to suffering daily—our patients’, our colleagues’, and our own. This has been magnified over the last few weeks as we are navigating uncertainties and change. The weight of this responsibility can be immense, making it all too easy to either become overwhelmed or emotionally detached. Rabbi Sharon Brous, in her recent book The Amen Effect, reminds us of a powerful alternative: to honor suffering, move through it, and embrace healing as a communal act. She talks about not only bearing witness, but also bearing with-ness, to highlight the importance of maintaining connection during difficult times.

Through a series of relatable stories in the Amen Effect, Brous describes the act of showing up for one another in moments of pain and joy, acknowledging suffering rather than turning away from it. She describes an ancient pilgrimage ritual where hundreds of thousands of Jews would travel to Jerusalem to climb to the Temple Mount plaza where they would turn to the right to circle counter-clockwise. Those who were grieving, lonely or sick would embark on the same journey, however, once they reached the plaza they would turn left to circle in the opposite direction. As each person traveling right passed a bereaved, sick or lonely person, they would pause to look them in their eyes and ask "What happened to you? Why does your heart ache?" This practice allowed the mourner to share their pain, to feel seen, and then to receive a blessing validating that they are not alone in their suffering; in fact, they are surrounded by community. This beautifully illustrates the power of connection and our common humanity. This principle is vital for physicians. We are often so focused on healing others that we neglect our own need for support, reflection, and restoration. But true strength doesn’t come from avoidance—it comes from facing hardship with openness, processing grief and stress, and finding ways to replenish our own spirits.

As healers, we must allow ourselves the same grace we extend to our patients. This means seeking out supportive communities, engaging in meaningful reflection, and embracing practices that sustain us—whether through mindfulness, connection, or simply giving ourselves permission to feel. Honoring our own suffering is not a sign of weakness but a step toward sustainability in both medicine and life.

This week, consider where you can acknowledge pain, show up for yourself or a colleague, and create space for healing. Only by tending to our own well-being can we continue to care for others with presence and compassion.

Dr. Michelle Owens-Kumar

mowensdo@gmail.com

Submitted February 2025

by Richard DeBehnke, MD

Medicine’s True Work: Building Trust

As I prepared to step away from the active practice of medicine, I was asked to provide some perspective on my journey. Ask my family, my peers, and my patients and they will confirm that I am more than willing to share.

Perspective tells me that we are not in the business of diagnosis, treatment, or procedures but that we are in the business of trust.

This is curious to me because my medical training never emphasized trust. It was my experience that the opposite was encouraged: C.Y.A. Instead, the emphasis seemed to be on ordering an excess of labs, never admitting a mistake, and in general doing anything and everything to avoid malpractice claims. Our patients were known as “heart failure in room 207,” effectively reducing someone’s loved one to an ICD 10 code. But we were smart, we were committed, and we took care of people.

As my career progressed, I struggled with finding the most efficient way to persuade patients that a course of treatment was necessary, reassure them while they were suffering, and help them accept the reality of their illnesses. How could one best take their knowledge and skills and do some good? In day-to-day practice how do you find success and reward in what you do?

I do not have answers, but it seems obvious to me that trust is involved. Without it, medical care seems impossible. Miraculously, trust seems to exist, but where did it come from and what did I do to deserve it from my patients?

How do you get someone to trust you?

Hemingway was quoted as saying, “The best way to find out if you can trust someone, is to trust them.” It is humbling to realize the people that step into our exam rooms do just that. They take a chance on us. How did we earn this generous gift? By being right all the time, curing every illness, or performing procedures no one else could do? We know this is not what happens. What are the step-by-step directions to acquire this ability, the conscious changes to make, or the places to go to uncover these mysteries? Can any of us say when it happened? Was it always there?

The other side of this beautiful dynamic, which rewards us as much or more than it does our patients, asks: If we are trustworthy, are we trusting? If our patients have the traits of a trusting person such as reliability, patience, openness, vulnerability, and honesty, do we share the same traits? Are we as open and vulnerable with them as they are with us? Can we really care for anyone without making that connection of trust, letting them know that not all of our experience comes from textbooks or seminars, but from walking the same paths that they have? Are they really just looking for a partner to walk the road with them, guiding them around most (but not all) pitfalls, and being there to help them up when they stumble? From these fellow travelers we receive the thanks, loyalty, and respect that make our work meaningful. Reflecting on all the books we have read and shows we have seen, haven’t we sat in rooms and heard real stories just as dramatic and poignant? “Can you help me?” may be the highest praise one person can give to another.

I believe what is most important to the people we care for is not getting it right but getting them.

Finishing this I am struck by the number of questions I have asked, so obviously this is not a guide or set of instructions. But I am confident in saying that we are purveyors of trust, and I encourage you to open up and trust your patients, your peers, and most importantly, yourselves. Perhaps all this is just a personal reflection on my career. If so, I hope reflection implies that a little light and some focus has been generated along the way. That would be good enough.

Dr. Richard DeBehnke

debehnker@gmail.com

Submitted February 2025

By Lauren J. Crawford, MD

Moving Meditation & Revisiting Fight Club

Fight Club is a 25-year-old movie that is raw, irreverent, thought provoking, and clumsy. For me, it’s also nostalgic. Movie magic for a college student. I watched it again recently. The movie still resonates but for different reasons and through the lens of an older eye.

I’ve been asked twice to write for our wellness group. I give a wry smile and say ‘Sure!’. The truth is that I’m not good at wellness. I’m like a wellness dropout. I’ve done one therapy session in my life after my mom died and I found it awkward and hard to focus. I stupidly can’t meditate, and a long session of gentle yoga has the opposite effect of what’s intended.

But I’m good at looking at a hectic physician’s life and figuring out how to lighten the load and make it easier. Working to build egalitarian households, spending money wisely to offload home stressors, and saying no to unsustainable workplace practices are the big ones. Making life easier before you not just burn out but absolutely flame out. I have learned a few things in 15 years of practice.

Another big one – carve out time for your fitness and do not ask for permission to do so. Your kids will be fine. Let them have 30-60 minutes of a 1980’s childhood. Spoons will go missing. A giant hole will get dug in the backyard. They’ll probably live.

I learned a phrase about wellness where I found success and it stuck with me. Moving meditation. It’s the best tool in my toolbox for making me feel well. And, I bet I’m not alone. I’d also be willing to bet that there is a form of moving meditation that helps everyone. You just have to find your own groove.

For me its running and sometimes running to near exhaustion. Don’t worry folks, I don’t do this on OR days but all the other days are fair game. This is where my interest in Fight Club resurfaced.

I am Jill’s hypothalamus. Although I can enjoy it, walking doesn’t work for me. Running a moderate pace helps me focus on a problem and work on solutions because it dims the peripheral noise. Running hard or super long makes everything go quiet and primal. Maybe it’s because my body is so focused on surviving it. Maybe it’s the endorphins and other neuro signaling. It’s such a nice feeling to tune out all the noise except the immediate environment, my feet moving, and my muscles complaining. It depletes creative thoughts, but also the malingering worry. I sleep hard.

‘No distractions. The ability to let that which does not matter truly slide.’

I don’t look good either. I look basic and sweaty. Sweaty in a gross way, not in the rich pine-smelling sauna way. It’s good to lean into that every now and then when the world around us constantly creates content to help us approach perfection. It may be strange to hear this from a plastic surgeon but even plastic surgery doesn’t get you there. Lighting, makeup, filters, angles. It’s good to just exist in your skin and let yourself be imperfect.

‘After fighting, everything else in your life got the volume turned down.’

After the run, the effect does hold. After something challenging, I’m physically done but also the most mellow soul in the world. Beer thirty with no beer. Consistent work really infuses that mental Zen into my life and my personality takes a dive when I can’t do my thing. I don’t think this is something that science has a good understanding of although we know that exercise can occasionally outperform meds and therapy for depression. For doctors, I think it can temporarily drown out the bad clinic experiences, the frustration with an administrator, and even just the busy worker bee mentality to constantly chase productivity. We all need breaks even if we can’t find all the solutions in a day.

‘Being tired isn’t the same as being rich, but most of the time it’s close enough.’

I encourage everyone to find something relatively intense that uses their body that they hopefully like to do. Dirty minds may go where they wish. For others I imagine it could be dancing. The kind of dancing where distraction means you end up on the ground. Challenging rowing, yoga, rucking, or actual boxing. Choose your own adventure. But it has to be accessible and not a novelty because you have to do it with some frequency. And, you have to mostly like it. After 8 or 12 weeks, maybe it’s a habit.

Good luck with your very own moving meditation. Maybe a skosh less intense than fight club and with a side of better coping strategies. I highly recommend it.

Signed,

Jill’s Prefrontal Cortex

Dr. Lauren J. Crawford

laurencrawfordmd@gmail.com

Submitted February 2025

By Dr. Tina Philip

Change

“In any given moment we have two options: to step forward into growth or step back into safety.” - Abraham Maslow

For as long as I can remember, change is something that I have dreaded. I have always been a creature of habit and am most comfortable in my predictable routines. I wouldn’t consider myself a highly anxious person, but I definitely experience some apprehension when things don’t go as planned.

March 16, 2020. Most of you probably remember this time frame as when the pandemic became a reality for us here in central Texas. I remember this specific date as the day I opened the doors to my brand-new solo practice. Four days later, those doors “closed” as shelter in place orders went into effect. Talk about things not going as planned.

For many years prior, I had thought about changing my practice situation. I began to interview for other jobs, but I was fearful of change. What if a new job is worse than the one I already have? I did interview after interview, finding fault with each one because it was not exactly what I wanted. I realized that if what I wanted did not exist, I would have to create it myself.

Then the fear of starting a practice set in. What if I failed? What if it was too hard? I began the arduous process of building a practice. There was a cautious optimism as I started to make decisions on what my future practice would look like. Each step away from comfort was a step in the right direction, even if it did not feel like it at the time. Of course, planning for a global pandemic was not part of my business plan, but as it is with many other challenges in life, I rolled with it. It was daunting opening a new practice amid such uncertainty, but I was determined to press forward despite the challenges.

As you read in last week’s Sunday email, Dr. Brian Sayers has stepped down as chair of the Physician Wellness Program. When I first read it, I had a lot of feelings, the main one being sadness. In the TCMS Physician Wellness Program he has created something unique, the likes of which cannot be replicated, and for that, I cannot thank him enough. In a time where so many of our social connections seem superficial at best, the multiple facets of PWP have created tethers to something real; something that reaches the humanity of being part of this family of medicine. He has put himself into this program in more ways than any of us can fully understand. How can this program possibly continue without him in charge?

Then the reality of assuming care of this program in the interim set in. There is a lot of fear attached to taking responsibility for something so important to so many people and trying to fill some very big shoes. What if these emails stop speaking to people? What if I mess up this program? What if this program loses its spark? The answer to such natural worries is that our efforts will be guided by the TCMS Foundation board, and the program will continue, perfectly or imperfectly, to focus on the many needs of physician well-being.

I fully believe that everything happens for a reason and in its own time. As uncomfortable and unwanted as it is, change is necessary for the growth of this program. Maybe the point is not for the program to continue to exist as it is, but to continue to evolve and support the needs of our ever-changing physician community. Ultimately, while the Foundation board is its steward, the Physician Wellness Program belongs to our physician family. Although it will not be the same as it was under the familiar warmth of Brian’s leadership, I am cautiously optimistic that it will be what we need, because we will grow it together.

Tina J. Philip, DO

President, TCMS Foundation Board

tina.philip@gmail.com

Submitted January 2025

By Dr. Brian Sayers

Pilgrimage

In 1969 ethicist Paul Ramsey delivered a series of lectures sponsored by Yale Medical School and Yale School of Divinity, later published and widely disseminated, ushering in the era of modern medical ethics and bioethics. I came across my copy of it recently, dozens of Post-It tabs highlighting specific areas that meant something to me when I read it more than a decade ago in seminary. One particular line has always stuck with me: “The practice of medicine is one such covenant. Justice, fairness, righteousness, faithfulness, canons of loyalty, the sanctity of life, hesed, agapé or charity are some of the names given to the moral quality of attitude and of action owed to all men by any man who steps into a covenant with another… explicitly acknowledges that we are a covenant people on a common pilgrimage.” Whether viewed through a religious or secular lens, the idea is clear and gives us an admittedly idealized view of the doctor-patient relationship.

It got me thinking about the nature of the doctor-patient relationship. This partnership is critical to keeping both patient and doctor emotionally healthy and keeping both fully engaged in achieving optimal medical care. But this relationship can be a moving target in a rapidly evolving healthcare environment with the rise of medical consumerism and the ease at which our patients can research and become more active participants in medical decision-making. Described another way, “this relationship has been profoundly shaped by the human rights movement of the past several decades, and clinical care today is guided by norms of shared decision-making rather than benevolent paternalism.” Understanding, honoring, and navigating each individual patient’s desires and understanding of this relationship is critical in a working partnership with patients. Emphasis is now usually placed on patient satisfaction within this partnership, often emphasizing the physician’s bedside manner, but increasingly we also realize the importance of this relationship to the health of the physician. In the end, we will all have played both the role of physician and patient.

Defining the key elements in bedside manner is often made more complicated than it should be. A group from Harvard Medical School described 4 key components: trust, knowledge, regard (friendliness, warmth, emotional support), loyalty. More recently, a great deal of emphasis has been placed on the level of empathy that is both heartfelt and tangibly evident when a physician cares for a patient. There is great truth in this: a sense of understanding, of “shared suffering” is indeed what we all need to different degrees throughout our lives. In his landmark article, “The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine,” Eric Cassell notes, “the relief of suffering and the cure of the disease must be seen as two obligations of a medical profession that is truly dedicated to the care of the sick.” Others have noted that although empathy is an essential characteristic of a holistic physician, it can be a two-edged sword that, when unbalanced or overdeveloped, can affect objectivity, judgement and can be a significant contributor to physician burnout.

A more basic understanding of the relationship between physicians and patients might just involve kindness. Kindness is hard to define, but easy to recognize. When you think about it, kindness encompasses all the critical components of covenant that Ramsey spoke about at that gathering of great minds a half century ago. The more I have thought about kindness and now try to write about it, the more I realize how far short of it I fall most days, and how often I see and admire it in my colleagues, including my own doctors. It’s easy to find yourself in a hurry or frustrated or distracted and fail to see the shared humanity, even suffering in its many forms right there in front of you and to fully honor that covenant, that common pilgrimage physicians and patients take together. Perhaps intentionally honoring that high calling more often than we miss, it might just be the difference between loving our work and just having a job.

The legacy that we slowly mold, then leave behind after a long, or even a short, career in medicine may in part be defined by our diagnostic or therapeutic acumen, but when I consider my colleagues, past mentors and teachers, I think it is defined in a more lasting way by the characteristics that bond us with our patients and colleagues − patience, fidelity, empathy, love, but especially kindness. Yes. Kindness. That just might be enough.

Brian Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

Contact Dr. Sayers at briansayers24@gmail.com

Submitted January 2025

By Dr. Robina Poonawala

The Truth about Penguins and Doctors

A sprawling city bustles with the loud racket of morning hour rush. Crowds of commuters hurry past each other. Suddenly, one traveler bumps into another and sets off a shouting match.

This might seem like a typical morning in New York City, but the location is Antarctica and these commuters are chinstrap penguins. Named for facial markings that resemble helmet chinstraps, these flightless two foot tall birds live in and around Antarctica and nest in crowded communities called colonies. Many chinstrap colonies are home to hundreds or thousands of individuals and have a lot in common with manmade urban centers and their inhabitants.

Every November near the start of summer in Antarctica, chinstrap penguins arrive at their breeding grounds. There, they begin construction work. Mated pairs use pebbles to build nests that are up to 20 inches wide, like human neighborhoods arranging their nests side by side. They live in close quarters for safety ‒ a lone nest would be a sure target for skua, a predatory bird that swoops from the sky to snatch chinstrap eggs or chicks.

While penguins have evolved from flying birds, their superpower lies in being the best divers of all birds. To protect from the cold, they have dense feathering, and different species are distinguished by the colors of their heads. Female penguins lay one or two eggs and both parents take turns caring for the eggs. While one stays behind to keep the eggs warm and safe from predators, the other heads out to sea to feed on krill, fish, and squid. Once hatched, they are carefully watched for around three weeks when both parents may have to leave to forage for food while their chicks gather in the safety of the larger group of other young penguins called crèches for warmth and protection. This shared labor is so important that a penguin chick will not survive if it has only one parent. Chicks who are hungry may beg from other parents but there is no fostering, and adults will only feed their own offspring.

By March, when the chicks are nine weeks old and their downy baby feathers have been replaced by waterproof adult feathers, they plunge into the sea and forage for their own food. Mated penguins use calls to identify each other and their offspring. The penguins are monogamous and return to the same breeding partner year after year. As far as scientists can tell, there are no couples therapists or divorce attorneys in the colonies.

Observing penguins reminded me of the importance of community. We all need connection with each other for communities to survive and prosper and for our children to thrive in their formative years.

We feel security and a sense of contentment when we are with our peers ‒ the human version of the warmth and security that penguin communities model. Just as the penguins huddle together to survive harsh weather, shortage of food, and predators, together in community physicians and their families survive and thrive in spite of a wide variety of challenges, even predators, that we face daily as individuals and as a profession. We just have to stick together!

Dr. Robina Poonawala

Send comments to Dr. Poonawala at robina.poonawala@gmail.com

Submitted January 2025

By Dr. Brian Sayers

Real Change

When this comes out on January 5, there’s one thing we can count on: most New Year’s resolutions have already been abandoned. New Year’s resolutions fail because they are usually quick fixes for bad habits or other problems that involve a solution that is no fun and that we aren’t really all that serious about, often changes that involve weight, exercise, diet, alcohol, or spending. The plan, if it can be called that, typically overestimates the effectiveness of willpower, of muscling through a firmly entrenched behavior pattern, often ignoring the reality that change requires not just bulldozing over entrenched behavior, but actually understanding the behavior and why it makes us unhappy even as we persist in doing it. What some authors call “real change” is, well, real hard. It involves the big things in our lives that stand in the way of contentment, meaning, or honoring our deepest beliefs.

Real change isn’t hatched in a vacuum. It is usually a response to a sense of unease or sadness or yearning. The spark that starts the fire can be anger, grief, regret, shame/guilt, bad habits/addiction, relationship problems or loneliness. Each of these are serious internal feelings that must be explored, their roots understood for lasting change to be possible. One of the most rewarding aspects of working with physicians in PWP these last few years has been to witness and fully appreciate our capacity to make meaningful change. We see it in a variety of life-changing expressions − in committing to recovery, in reclaiming their calling by changing their practice setting mid-career, in seeking counseling, and sometimes by either saving or stepping away from a failing marriage. Willingness to change is an essential part of any life, but not an easy one. Theologian and ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr once noted, “Change is the essence of life; be willing to surrender what you are for what you could become.”

Real change starts with a careful assessment of what is not right with our life. The path toward change requires careful discernment in the context of our values, our relationships, what makes us feel content, and how a problem tangibly affects our day-to-day life. From this can emerge a carefully considered plan for a long-term change of course rather than a quick fix. Successful, real change is usually measured in months or years, through a series of innumerable small steps (and missteps).

When fully achieved, real change is a seismic movement of the soul, a visible expression of our values − what lies within our heart. With a sincere desire for change, as Sharon Salzberg notes “…. the engagement that results can be an openhearted demonstration of what we care about most deeply. Efforts toward change are an expression of our own innate dignity and testaments of the belief that what we do matters in this world. We engage not only to try to foster change right now − we engage to enliven what we believe to someday be possible.” In what Mary Oliver calls our “one wild and precious life,” we have been given many gifts, among them our sense of purpose, connection with others, grace, and an innate capacity for change − again and again − as we travel through this life in this world.

Brian Sayers, MD

Chair, TCMS Physician Wellness Program

Contact Dr. Sayers at briansayers24@gmail.com